Part Three

THE BIRKENHEAD SUGARWORKERS UNION: A MICROCOSM OF NEW ZEALAND’S SOCIAL LABORATORY

by Angela Black*

In historian circles and popular consensus alike, New Zealand is often hailed the “social laboratory of the world”. Despite harbouring a population of only 5 million, Aotearoa has in many ways been a leader in the areas of social and democratic reform. In 1893, New Zealand made headlines in becoming the first country to grant women the right to vote in parliamentary elections. In 1898, it introduced the old age pension, affording a small tax-funded allowance to elderly people “of good moral character”. In 1938, the First Labour government introduced the Social Security Act, establishing unemployment and disability benefits for the needy and universal free healthcare for all New Zealanders.

Chief amongst these reforms, although perhaps less well-known to New Zealanders, was the introduction of a series of labour legislation by the first Liberal government in the 1890s. Spearheaded by the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act of 1894, this legislation was designed to ensure fair working conditions and put an end to strikes by encouraging employee-employer negotiations and requiring any disagreements to be settled by the Arbitration Court. The merits and downfalls of such a system are beyond the scope of this essay. What is clear, however, is that an examination of the workings of the Birkenhead Sugarworker Employees’ Union to improve working conditions and industrial relations can provide us with a case study as to how these labour laws were put to use in factories throughout New Zealand.

The First Birkenhead Sugarworks Employees’ Union: 1901-1911

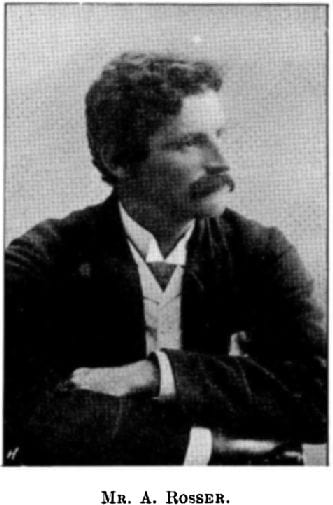

Neither working conditions nor industrial relations were first-rate when the first Birkenhead Sugarworks Employees’ Union was registered under the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act in 1901. Wages were already low and the Colonial Sugar Company was threatening to reduce them even further. The average working week was 54 hours over the course of 6 days and often involved tough manual work in sweltering conditions: one worker in the char house described how the heat in the factory reached 104 degrees celsius (40 degrees celsius). Meanwhile, the Company largely turned a blind eye to the workings of the union, refusing to acknowledge the externally-sourced union secretary, Mr Arthur Rosser, and prohibiting the union from meeting on Chelsea grounds. Additionally, there were allegations that the Company occasionally dismissed men with less than 24 hours notice for no other reason than their involvement with the Union.

Mr Arthur Rosser, the first secretary of the Birkenhead Sugarworkers Employees’ Union. Image governed by Creative Commons Share-Alike Licence – Courtesy of the New Zealand Electronic Text Collection, “Mr Arthur Rosser.” Accessed February 26, 2022. http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc02Cycl-t1-body1-d1-d16-d7.html.

These tough conditions and hostile attitudes from the Company paved the way for the union to employ the mechanisms of compulsory arbitration, as set in place by the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act. On January 20th, 1902, after failing to engage the Company in negotiations, the union filed a dispute which was to be taken to the Arbitration Court. This process proceeded exactly as intended by the creators of the Act, providing parties with a state-mandated alternative to engaging in aggressive industrial action. As per the Act, the Court heard witness evidence called by each party before producing an industrial award that stipulated various conditions of employment.

The union brought several demands to the Court. They asked that the work week be brought down to 48 hours over the course of 6 days, with overtime paid at time and a quarter for the first two hours and time and a half thereafter. Sundays and public holidays should be paid double time. It was also stipulated that the minimum wage should be raised to 3 pounds for the 48 hour week, with several workers citing high costs of living: George Mayall had been working a 54 hour week for 2 pounds 2 shillings whilst his household expenses often reached over 2 pounds 4 shillings. The union also asked that a preference clause be inserted into the award. This clause was a common yet controversial demand of unions. It would require the Company to employ union members in preference to non-union members with the same skillset, ensuring that any non-union members willing to accept lower pay or longer hours did not undermine the award.

Overall, the proceedings were a relative success for the union. On December 23rd 1902 the Court delivered their award, which was to take effect from January 1 1903. The working week was brought down to 48 hours, although the Court left the Company in charge of deciding how these hours were to be arranged. The Court also granted the preference clause, noting that practically all workers were already part of the union and that this clause was in no way against the best interests of the Company. However, contrary to the wishes of the union, the Court refused to raise wages. Instead, it stipulated that the same wage should be paid for the 48 hours week as the Company had been paying the workers for their 54 hour week. In the words of the Court, “these rates being in our opinion not all too high for a week’s work of 48 hours”.

Although we know very little about industrial relations in the years following the 1903 award, it seems clear from a union decision of 1906 that these had at least somewhat improved. In 1905, the union filed demands for a new award. In the meantime, owing to delays in proceedings at the Arbitration Court, the union held “two or three” conferences to attempt negotiations with the Company. In May 1906, the union instructed their secretary, Mr Rosser, to withdraw the case pending in Court. The Company had agreed to raise wages by 3 shillings a week. Despite Mr Rosser’s warnings that this private agreement would not be binding by law, the union “had confidence that the company would carry out the agreement”. Additionally, a company delegate relayed that the “aim was to work hand in hand and man to man”.

The relative success of the first Birkenhead Sugarworkers’ Union in properly utilising compulsory arbitration to their advantage and improving industrial relations was short-lived. In July 1911, amidst a period in New Zealand’s history which was plagued by anti-arbitration sentiment, the union’s registration under the I. C. &. A. Act lapsed. With this demise also came the lapsing of the Court’s 1903 award, which in effect left it up to the Company to decide whether or not to continue to afford workers the conditions of employment which had been stipulated. For the next 9 years, including through World War I, there was no union to represent the workers at Chelsea.

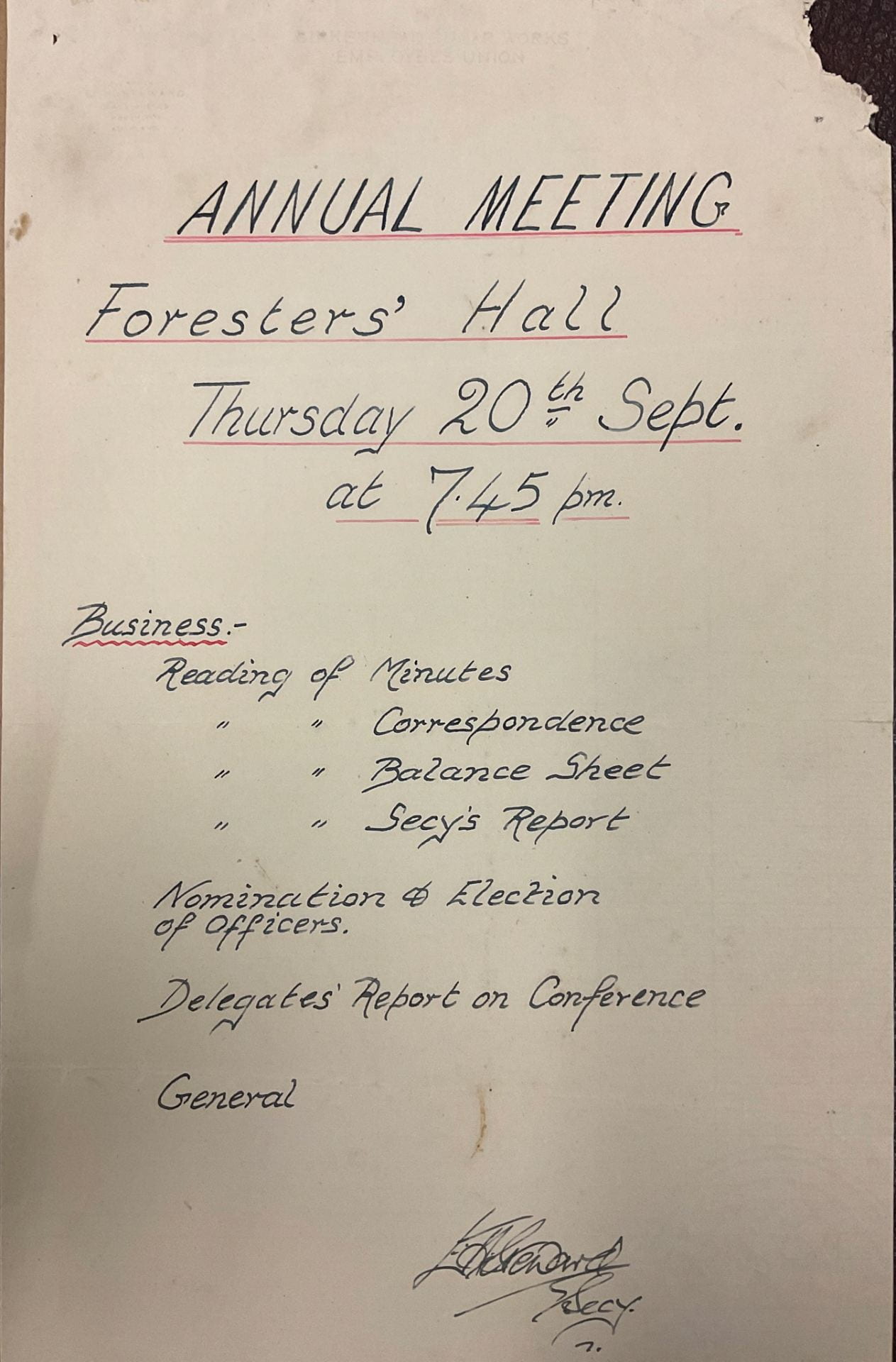

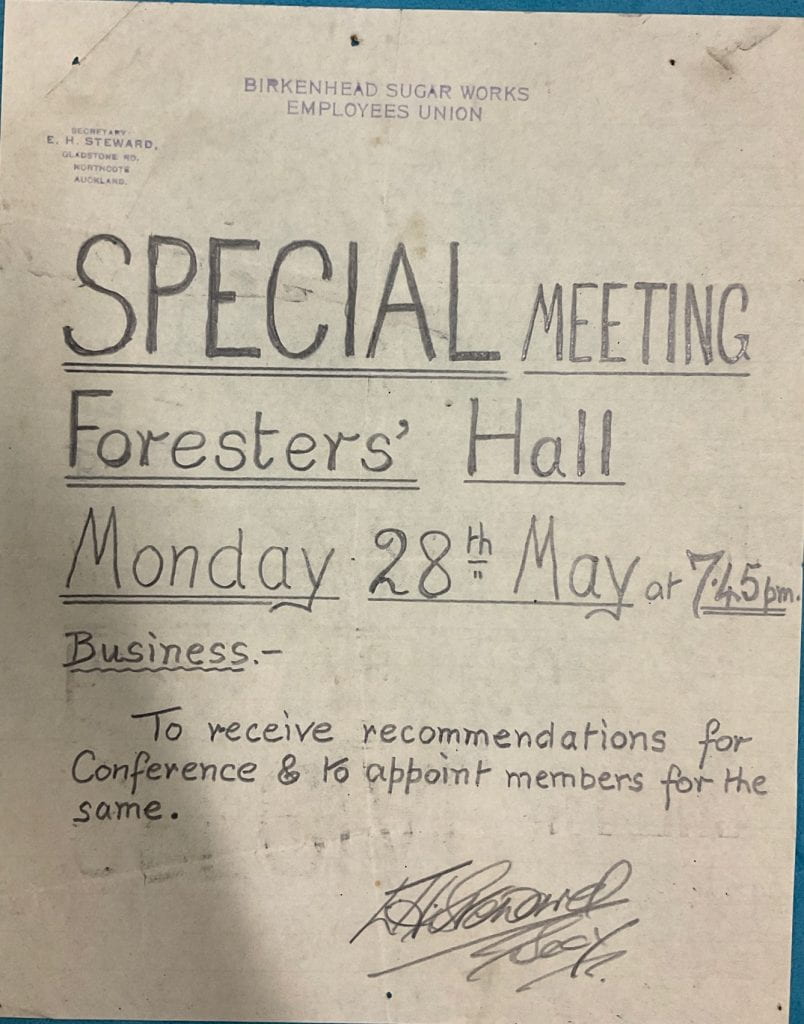

Meetings of the Birkenhead Sugarworkers Employees’ Union were held regularly at Foresters’ Hall in Birkenhead. Image Courtesy of Special Collections: University of Auckland.

Reregistration and the 1920 Strike

In 1920, the Birkenhead Sugarworkers Employees’ Union rebanded and once again registered itself under the I. C. & A. Act. Unlike its predecessor, the new union got off to a rocky start. Soon after its inception the union deferred from its commitment to compulsory arbitration under the I. C. & A. Act and organised the only major strike in the history of the Chelsea Sugar Works.

Chelsea Sugar Factory staff pictured in 1919, one year before Chelsea’s only major strike in 1920. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections B0461.

The dispute which led to this strike began on July 2, 1920, when the union requested a conference with the Company to discuss a proposed decrease from a 48 to a 44-hour week and a 1-pound increase in the minimum wage from 3 pounds 14 shillings to 4 pounds 14 shillings. After initially refusing to meet in conference, the Company filed a dispute in Court. A conciliation council was set up but to no avail. The Company refused to submit to a 44-hour week and was only willing to raise the minimum wage by 6 shillings.

What transpired next was a series of tit-for-tat actions performed by both the union and the Company. On August 14, union members walked off the job at midnight. On August 18, the workers declared an end to the strike after gaining assurance that the Government would not oppose their demands if they resumed work and let the dispute be taken to the Arbitration Court. However, with no raw sugar to treat and their machinery having been dismantled for repairs, the Company delayed the recommencement of work. When the Company later invited men to resume work, it declared the right to refuse to re-employ some strikers. In response, the union announced its intentions to continue striking until all men were invited back.

In the meantime, the Arbitration Court had commenced an early sitting to hear the claims of both parties in response to the proposed award. The Company, opposing the 44-hour week, noted a government contract which required them to refine 65,000 tonnes of sugar per year – a task which was not even being met under the 48 hour week. The union assured the Court that a reduction in hours would not lead to a reduction in output. On September 17th 1920, the Court delivered its award. The working week was reduced to 44 hours and the minimum wage raised by 6 shillings to 4 pounds. On September 20th 1920, the Monday following the announcement of the award, the strikers finally returned to work.

Although the strike culminated in workers gaining a shorter working week and a slight increase in wages, the effects it had on the company and the general population are indicative of the reasons the Liberal government introduced the compulsory arbitration in the first place. The strike cost the company five weeks’ worth of revenue and had a scathing impact on the sugar market in New Zealand. Shortages forced retailers to resort to strict rationing and some manufacturers in the confectionery, jam and biscuit industries temporarily closed their doors.

These repercussions were not lost on the public, and presumably recognised by sugar workers as well. On September 21, 1920, the New Zealand Herald published a scathing attack on the strikers under the headline “The Strike Discredited”. Labelling the strike “futile”, “folly” and “an unwarrantable attack on the community”, the author did not hold back reprimanding the men responsible:

“Against their losses, the sugar workers have not a single consolation. The terms on which they have returned to work could have been framed without any interruption to the industry. Thus the whole effect of the strike, so far as its authors are concerned, has been the humiliation of the union’s members, and so far as the public is concerned, an unnecessary and inexcusable infliction of inconvenience and hardship”.

Indeed, the 1920 strike would prove to be the first and last major strike in the history of the Chelsea sugar works. In the years to come, the union returned to resorting to the mechanisms of conciliation and arbitration to settle disputes. In 1926, the Court awarded another wage increase to a minimum of 4 pounds 1 shilling. After a quick 10% wage cut during the depression, another 5-shilling wage increase was awarded in 1937. In 1934, in a letter justifying the existence of the union to anti-unionists, secretary E. H. Steward expressed his appreciation for the I. C. & A. Act by stressing the benefits afforded by its ability to obtain legally-binding awards.

Alongside this return to the mechanisms of conciliation and arbitration after the strike, union records suggest that industrial relations during this period also slowly but surely improved. In a correspondence between the union and the company in 1928, the union noted how “a very antagonistic feeling existed” between the parties at the union’s inception. In contrast, the correspondence rejoiced in the fact that “it can [now] be truthfully said that our members feel that the relationship with their Employers was never better”. This sentiment was further echoed in 1934, in a letter in which the union thanked the Company for not taking advantage of an amendment to the I. C. & A. which allowed them to reduce wages. Union secretary, Mr Chandler, suggested that the Company’s decision “has done much to foster the spirit of cooperation and cement the goodwill that exists between the Company and its employees”.

Overall, this history of Chelsea Sugar Factory and its associated union is not an isolated one. Instead, it is one which has ties to broader events and movements which have shaped both the nature of New Zealand’s industrial relations today and influenced New Zealand’s international reputation as the world’s “social laboratory”. The Birkenhead Sugarworks Employees’ Union’s interaction with the I. C. & A. Act and compulsory arbitration is just one example of how the events which took place in the questionably-coloured buildings which make up the Chelsea Sugar Works interacted with a wider cause. To lose the buildings would be to lose a sense of a space in which many aspects of the labour movement played out.