Part Five

The effects of the Waikato War on Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua

Part Three

The fluidity of Ngāti Te Ata rohe

by Tommy de Silva*

In this series of articles, I have aimed to demonstrate the fluidity of historic Māori society, using Ngāti Te Ata as my case study. I have explored the flexibility of rohe (territory), thought, and action to dispel myths about tangata māori having lived rigid and unchanging existences. In contrary to the demonstrated fluidity of historic tangata whenua, the actions of the historic Crown were largely uncompromising in its definition of ‘enemy’ following the Waikato War. It is likely that the leaders of Ngāti Te Ata who secured friendly status with the Crown, would have expected to be exempt from the ill-effects of the war, much like they were exempt from Grey’s proclamation before the fighting commenced. But, as Vincent O’Malley acknowledged, there was no real benefit to historic Māori in working with the Crown. In actuality, Ngāti Te Ata felt the full force of the Crown’s wrath after the war, with little concession being granted due to their friendly status.

In a letter written in December 1860, Crown informant and local Pākehā, Henry Halse was equal parts poetic and prophetic, if prophecy is to be interpreted oppositely. Written during the first Taranaki War, Halse explained, “I found natives here under an impression that so soon as the tribes in war against us are subdued, we shall seize the whole country to pay expenses of the war, and so punish the innocent, as well as the guilty. I set them at rest on that point and wished them to make it known that so long as the natives took no part in the war and remained at peace, no one would be permitted to harm them.”. But Halse’s assurance did not ring true. All of Ngāti Te Ata, both enemies and friends to the Crown, felt the brunt of its post-war policy. As such, the Crown was largely inflexible in who it saw as its enemy. Undoubtedly that there was no place for friendship within the systematic and indiscriminate oppression required for British colonisation.

Short term effects of the Waikato War on Ngāti Te Ata

As was discussed in my last article, many Ngāti Te Ata were captured during the Waikato War and had to endure captivity in horrible conditions, like those aboard the prison ship Marion. Sickness was rife among the prisoners on board the Marion affecting most. Not only were members of Ngāti Te Ata imprisoned during the war, but undoubtedly some were killed, as is the inevitable, yet wasteful, cost of war. Although it has been difficult to ascertain exact casualty numbers for Ngāti Te Ata during the Waikato War, every single death was significant as it meant a devastated whānau, hapū and wider iwi. Even on the home-front, members of Ngāti Te Ata felt the destructive force of the war.

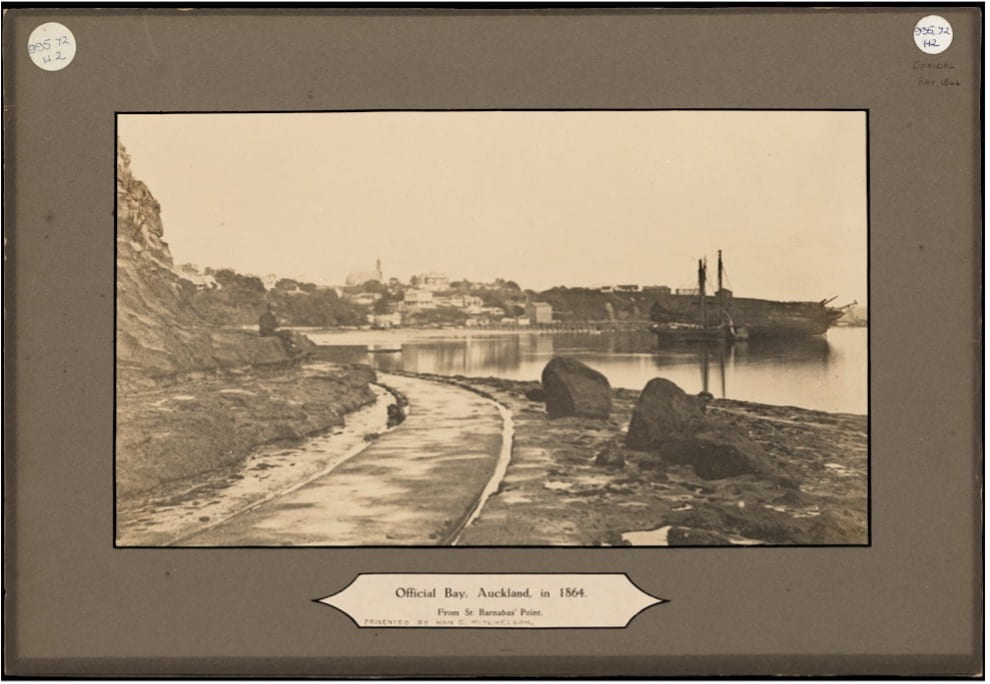

The ship moored on the right is probably the Marion. Clearly a ship of that size was not fit to house over 200 prisoners of war in hygienic or humane conditions. Source: Unknown Photographer. 3-384 ‘Official Bay, 1864, showing Wynyard Pier, Britomart Point, and Old St Paul’s Church’. 1864. Digital file of print. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Heritage Images, Auckland.

My last post discussed a party of Ngāti Te Ata accompanied by Mr Puckey from the Native Department who destroyed a fleet of Waka in November 1863. Several members of that group were arrested at bayonet point two days later on 11 November 1863 by a force of the Waiuku Volunteers (a militia made up of local settlers and bolstered by special constables). En route to the arrest, the Waiuku Volunteers partly sacked Ahipene’s kainga at Kapiuta, dealing “a considerable amount of damage”. After the arrests, nine charges of suspected hostility towards the Crown were drawn up, seven of which were laid against members of Mr Puckey’s expedition. While these men were being arrested in their own homes, their property was also confiscated. A Daily Southern Cross correspondent reported that seven or eight guns, six tomahawks and several pouches of ammunition were stolen from the arrestees’ property. The arrested Ngāti Te Ata were then marched through the rain to spend a night imprisoned in the local militia fortification, known as a blockhouse. When they were finally released after being identified by Mr Puckey, their arms were never returned.

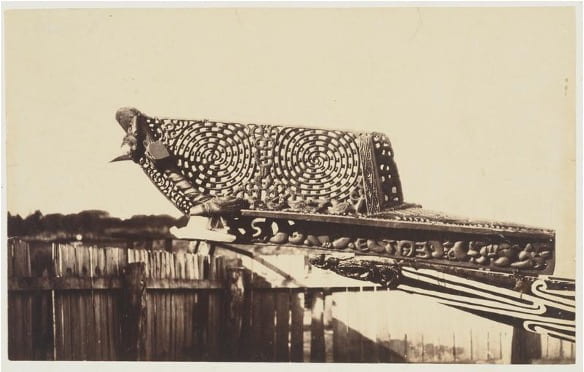

Also, on the home-front, many Ngāti Te Ata waka were destroyed by Crown forces. At a time when waterways played such vital communication and transportation roles, the destruction of waka would have been greatly detrimental to Ngāti Te Ata. From late October to mid-November 1863, local Crown forces destroyed or stole waka from within Ngāti Te Ata rohe on several occasions. During one July 1863 outing alone, 21 Ngāti Te Ata waka were destroyed or stolen. Included in the Crown’s haul of waka was the great waka taua (war canoe) Te Toki a Tapiri. This waka held significant cultural importance to several tangata māori groups. It was built by Ngāti Matawhaiti (hapū of Ngāti Kahungungu), carved by Rongowhakaata, both groups being from the east coast region, and it passed through the custodianship of Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Te Ata. Te Toki a Tapiri was recognised in 1863 as “one of the best finished canoes in New Zealand” , and today, it sits on display at Tāmaki Paenga Hira, the Auckland War Memorial Museum, as the last surviving great waka taua.

A photo showing an intricately carved section of Te Toki a Tapiri. Such exquisite whakairo (carving) was reserved for the most prestigious waka. Source: Kinder, John. 1983/22/15 ‘Tauihu, Waka taua Te Toki a Tapiri’. Ca. 1865-1868. Albumen on paper. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki: New Zealand Art.

Clearly, during the Waikato War, there was already distrust between Ngāti Te Ata and Pākehā that led the iwi to feel the ill effects of the Waikato War. Ngāti Te Ata occurring the wrath of the Crown so early indicates just how broad the Crown’s definition of enemy was. The Crown’s definition of “enemy” was uncompromising and extended somewhat to all tangata māori. Clearly, the Crown’s broad definition of “enemy” served its goal of superimposing rangatiratanga and mana with kawanatanga. Following the war, Ngāti Te Ata would continue to feel the Crown’s wrath.

Long term effects of the Waikato War on Ngāti Te Ata

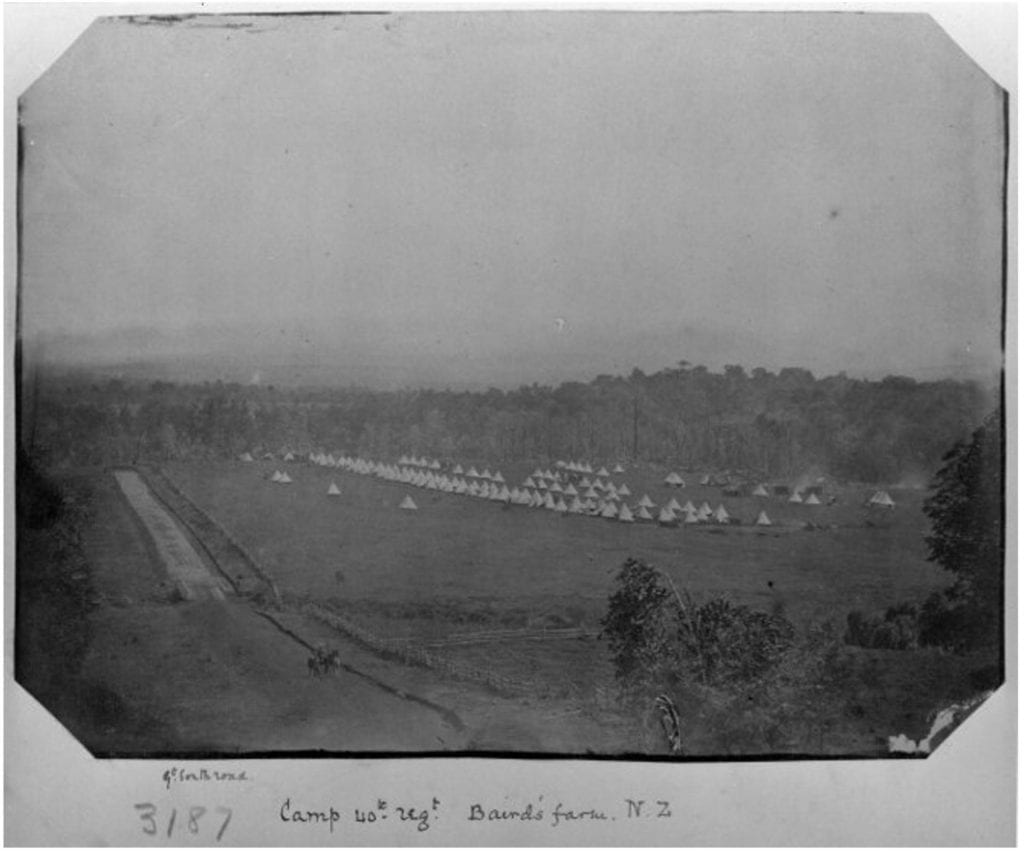

Although it was constructed to bring death and destruction upon Waikato tangata māori, the Great South Road would have an unintended negative impact on Ngāti Te Ata. As acknowledged by the Crown’s Deputy Quartermaster General, before the Waikato War, the completion of the Great South Road was a military priority. The road would be the Crown’s lifeline during the war as a means of transportation and communication. Bruce Ringer beautifully summarised the Great South Road’s military significance by saying that it “was indeed a dagger pointed at the heart of the Waikato”. After the Waikato War, the Great South Road became the preferred route south, bypassing the Awaroa portage. The Awaroa portage was an important part of the pre-war Waikato-Auckland trade route that ran through the Ngāti Te Ata heartland. This portage brought trade opportunities and with it economic opportunity to Ngāti Te Ata. Over time, bypassing the Awaroa in favour of the Great South Road alienated Ngāti Te Ata from the trade network that it had fruitfully engaged with for roughly two decades. With the Awaroa’s trade largely gone, coupled with the destruction of waka, the blossoming Ngāti Te Ata economy was dealt a crippling blow.

A Waikato War Imperial military camp in-between Drury and Bombay, just off the Great South Road. Source: Temple, William. Ref: PA1-q-250-34 ‘Camp of the 40th Regiment, Imperial forces, at Baird’s farm, Great South Road, Waikato’. 1863 or 1864. Albumen print. Alexander Turnbull Library: Urquhart album, Wellington.

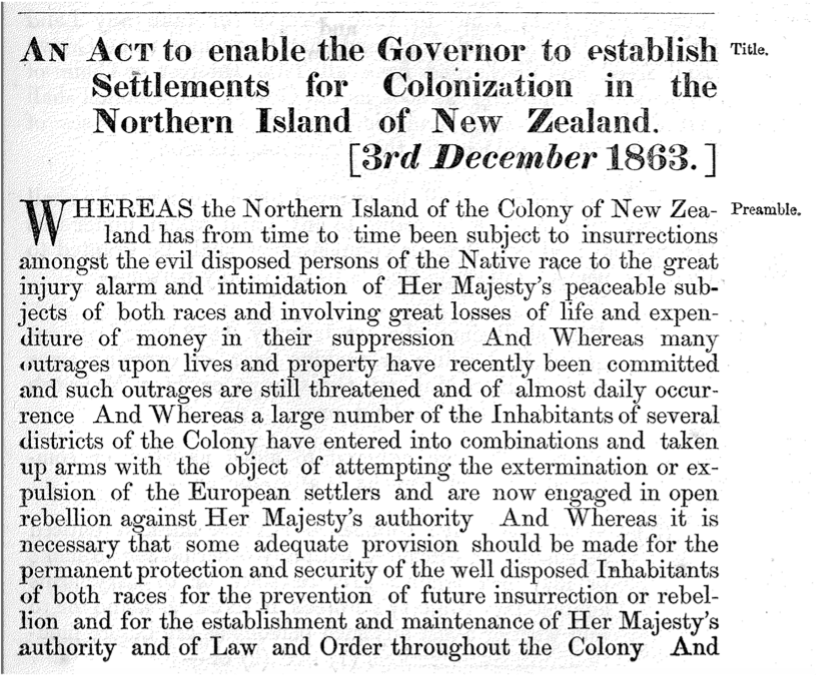

However, for Māori the most catastrophic consequence of the Waikato War was raupatu and its devastating effects. Raupatu traumatically affected Ngāti Te Ata. Raupatu was the Crown’s policy of land theft. The ‘Suppression of Rebellion Act 1863’ proclaimed that tangata whenua groups deemed to be in ‘rebellion’ against the Crown were to have their land confiscated. Further to that, on the third of December 1863, parliament passed the ‘New Zealand Settlements Act’ that outlined the measures and provisions for raupatu. The intended outcome of the Act was to alienate tangata māori who fought against the Crown from their whenua in order to establish Pākehā settlements. This Act dictated that confiscated land would be given to British settlers as Crown grants, but the Crown ultimately sold much of the land for profit. Crucially, the Act also permitted the land of friendly Māori to be stolen.

The preamble of the New Zealand Settlements Act. Note that it solely blames war on ‘the evil disposed persons of the Native race’ yet calls the Crown and its allies ‘peaceable’. However, also mentioned was that the Crown as of December 1863 still had to establish and maintain its authority. To me, this highlights that the Crown was not the established government of the day, and was in fact the rebel. Source: The Davis Law Library and Digital Services at The University of Auckland Library. 1863 > Public Acts > 8 New Zealand Settlements Act 1863. Unknown year. PDF scan. The University of Auckland Waipapa Taumata Rau: Early New Zealand Statutes, Auckland.

Through raupatu, Ngāti Te Ata were dispossessed of an “enormous” amount of land. On December 29 1864 alone, a combined 43,850-acres around Waiuku and Maioro were confiscated. Although much of this stolen whenua had already been ‘purchased’a, some of it was wahi tapū that had been previously reserved for tangata māori. The fact that so much Ngāti Te Ata land was taken through raupatu, even though the iwi was officially recognised as friendly, indicated the Crown’s broad definition of enemy.

From the seeds sown from raupatu, historic Ngāti Te Ata would have even more land taken once their land titles were individualised. In 1875, Ngāti Te Ata was reluctantly convinced by the Crown to forfeit all common land titles in favour of individualised titles. Moving on from common land titles split historic Māori land up into smaller sections with much fewer trustees than before this forced change. Consequently, there were fewer legally recognised claimants to any given land. As such, whenua could more easily be taken from tangata whenua because fewer individuals needed to approve ‘sales’. Raupatu and individualising land titles were vital Crown tools to appropriate tangata māori land. In reflection, if the Waikato War had had a different outcome, say a decisive Kīngitanga victory, it would have been at best impossible, or at least, very difficult, for the Crown to enact such measures.

It must be recognised in this narrative that under the New Zealand Settlements Act there was the provision for compensation of friendly Māori whose lands were confiscated. This provision begs the question: did the Crown have a degree of flexibility in who it saw as its enemy?

Potential signs of flexibility?

On 25 January 1865, compensation claims were opened for several areas in Manukau, including Waiuku. According to Bruce Ringer, by this date, Waiuku Ngāti Te Ata likely already had been promised the return of their possessions. As noted by the Commissioner of Native Reserves, On the confiscation, in 1865, of the West Waiuku block, the loyal natives then resident were promised that their villages, cultivations and burial-places should be returned to them, surveyed and under Crown grants”.

The year of 1865 saw Ngāti Te Ata receive some small grants, like the £465 of compensation given to the iwi in May. On 4 October 1866, the ‘Friendly Natives Contract Confirmation Act’ was passed, validating tangata māori grants for confiscated whenua. Bruce Ringer argued that this Act was specifically intended to legalise Crown compensation to Ngāti Te Ata. With the legal precedent set, by January the following year, Ngāti Te Ata received a compensation package that was coupled with payment for earlier land ‘sales’. Ngāti Te Ata collectively received £5,250 and 6,614-acres of land in compensation, among some individual grants as well. By 10 October 1867, Ngāti Te Ata members received a large part of a 1,396-acre compensation package. Compensation claims were not only heard for stolen whenua, as according to Dr Pollen, in 1871, claims were also opened for destroyed or stolen Waiuku waka. Some waka compensation was awarded, including £600 for Te Toki a Tapiri.

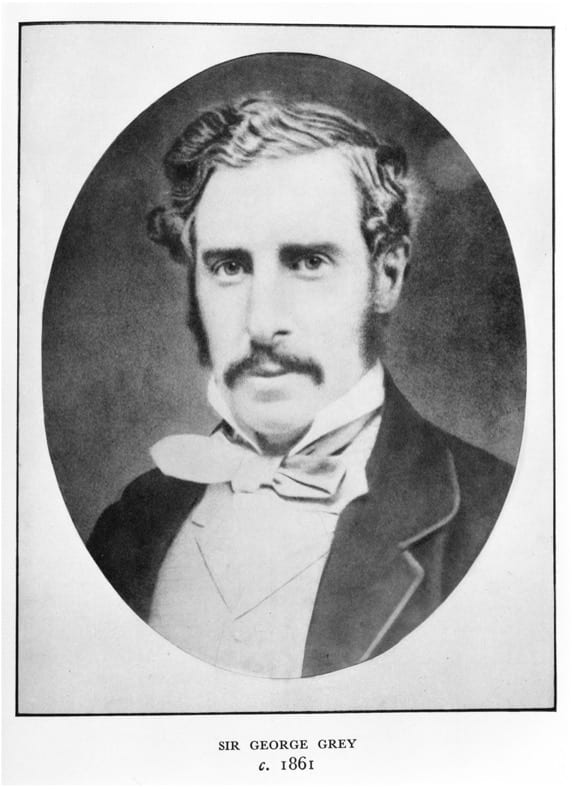

Alongside these compensation packages, Ngāti Te Ata was left off George Grey’s 1865 list of iwi who he intended to trial for ‘rebellion’ during the Waikato War. Do these Crown actions mean that it actually employed some sense of flexibility in who it saw as the enemy? I would argue no. When viewing the broader history, it can be concluded that even with the above compensation, with its questionable fairness, Crown actions still positioned Ngāti Te Ata as its enemy. As was previously mentioned, the Crown’s actions led to discrimination and outright hostility towards Ngāti Te Ata.

George Grey, a name that consistently arises when researching 19th century New Zealand history. Grey was twice governor of New Zealand during wartime which begs the question, why is he is not popularly remembered as a warlord as well as a politician? Source: Unknown photographer. 7-A3953 ‘Sir George Grey’. 1861. Film negative copied to a digital file print. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Heritage Images, Auckland.

Reflection on the Crown’s Actions

Not only were the grants received by Ngāti Te Ata minute in comparison to the real value of the confiscated land (typically less than 1% of the value), they ultimately also furthered the individualisation of land titles. The ‘Waiuku Native Grants Act’ passed on October 14 1876, cancelled the communal land grants of 1865 and replaced them with individual or whānau based grants. As previously mentioned, the removal of communal land titles was a vital and destructive tool of colonisation.

Further, Marama Muru-Lanning has argued that the land returned to tangata whenua in compensation packages was typically of poor quality and undesirable to the Crown. Also, some of the returned confiscated lands had already been reserved for Ngāti Te Ata, like the Maioro wahi tapu of Tangitanginga, Papawhero, Te Kuo and Waiaraponia. By returning already reserved land, the Crown was able to keep more of the new raupatu land from 1864.

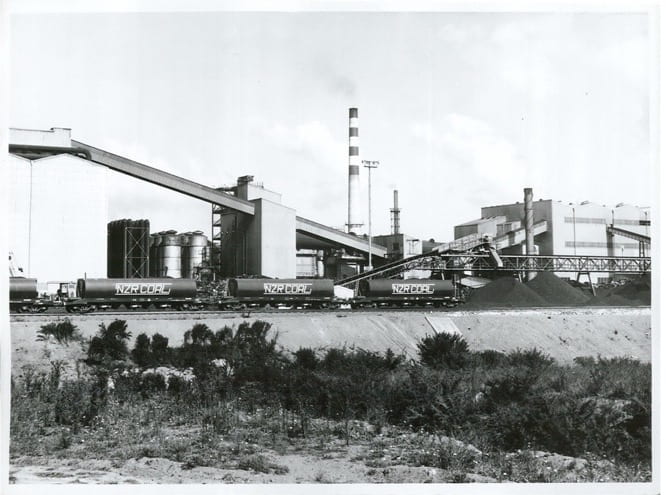

North of Waiuku sits the Glenbrook Steel Mill, here shown in its 1970 form. This mill is an eyesore on the otherwise picturesque view from the urupa at Tahuna marae. Over time, this mill has extracted iron-sand from Maioro, a place renowned for its ancient Māori burials, to manufacture steel. Source: Riethmaier, G. AAQT 6539 W3537 105 / A94480 ‘New Zealand Steel Mill, Glenbrook Auckland’. 1970. Photograph. Archives New Zealand: Flickr, Wellington.

Raupatu and the individualisation of land titles irreparably damaged the Ngāti Te Ata way-of-life. No level of compensation, money or small land grants, could make up for the Crown’s destruction of the Ngāti Te Ata way-of-life. Through alienating tangata whenua from their whenua, the wellbeing of both the tangata and the whenua was irreversibly harmed. Features of the Tāmaki landscape significant to Ngāti Te Ata have since been polluted, damaged, and desecrated. Matukutureia, the birthplace of Ngāti Te Ata namesake Te Ata i Rehia, was partly quarried to build the growing Auckland city. Forevermore, parts of the maunga where Te Ata i Rehia would have stood and looked out across Tāmaki Makaurau is inaccessible to her descendants. Te Manukanuka o Hoturoa, the ‘breadbasket’ for the iwi and hapū who lived on her shores, has been polluted from overuse and desecrated with sewage. Because the Crown purposefully alienated Ngāti Te Ata from its whenua in its pursuit of absolute hegemony in these motu, it is clear that Ngāti Te Ata, like all other tangata māori, were the Crown’s enemy.

Matukutureia birthplace of Ngati Te Ata namesake tūpuna Te Ata i Rehia. The traditional crescent shape of the maunga was destroyed by quarrying, as can be drastically seen in the upper left of this photograph. Source: Unknown photographer. Footprints 02137 ‘McLaughlins Mountain, Wiri, ca 1958’. 1958. Photograph print. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Heritage Images, Auckland.

Conclusion

Throughout this series, I have highlighted several examples of the fluidity and flexibility of historic Māori, with Ngāti Te Ata as my case study. I have examined the fluid rohe of Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua and its members’ flexible opinions, and subsequent actions. Yet, contrasting the fluidity of tangata māori is the inflexibility of the actions by the Crown. Although Ngāti Te Ata was officially listed as friendly during the Waikato War, in the decades following, the iwi would be ravaged by the Crown’s post-New Zealand Land Wars policy. However, Ngāti Te Ata endured the Crown’s onslaught, and today its members still occupy diverse parts of Tāmaki, showing resilience and an ability to adapt. Of particular note are the Waiuku Ngāti Te Ata and their kaumatua, who serve as the kaitiaki of our ancestral moana, Te Manukanuka o Hoturoa, preserving her for future generations.

Kupu Appendix

- Kawanatanga | The sphere of Crown ‘governance’, first agreed upon in Te Tiriti o Waitangi and later pervasively expanded upon by economic, social, legal and military conquest.

- Land theft | Typically, New Zealand history sources refer to land loss not land theft. However, the term land loss suggests that Māori themselves lost land like someone may lose a material possession, placing the agency for land alienation with Māori. In reality, Māori were not the agents of their own land alienation, instead the Crown systematically and purposefully stole whenua through legal, economic, social and military conquest. A redefinition of land loss to land theft is vital to understand the true reality of our nation’s dark history.

- Rebellion | The Crown promoted the narrative that tangata whenua groups fighting against them were rebels. However, by definition rebellion is a contest against an established government. During the New Zealand Wars, the Crown was undoubtedly not the established government, as is obvious by the fact that they had to enact conquest to gain sovereignty. In fact the established governments of the day were the independent hapū and iwi. As such, the Crown rhetoric of tangata māori being rebels is incorrect. In fact if any group was rebelling against the established governments it was the Crown.

- ‘Sales’, ‘purchased’ | These terms are emphasised within this series because to tangata māori no such purchases or sales ever occurred. Purchasing and selling are tauiwi (outsider) ideas that promote exclusive and restrictive ownership, and there were no equivalent concepts for them within te ao Māori. Tangata māori would never have conceived that by ‘selling’ their whenua to tauiwi that the land would then become inaccessible to them. Traditionally land was shared among kinship and allied groups. Tangata māori who ‘sold’ land to Pākehā believed that their, and their descendants, mana and kaitiakitanga over the whenua would not be extinguished through land ‘sales’.

Wahi Tapu | Sites that are sacred for a particular reason, for example, the presence of burials or it being a former battlefield where death occurred.