Part Four

Feminist Theatre Takes the Stage in 1980s Auckland

by Anna McCardle*

1980s New Zealand saw a “sudden burst” of women directing, writing, stage-managing, and acting in professional theatre, as reported by Priscilla Pitts in the feminist magazine Broadsheet. This increase and diversification of roles for women in theatre was underlaid by second wave feminism, a movement that took root in the 1960s to advance women’s rights and expand on the achievements of late 19th century first wave suffragettes. As actor Andrea Kelland remembered, “it [second wave feminism] had started overseas, but I think that ‘83, ‘4, ‘5… it came into its own in New Zealand.”

Feminism coming into its own motivated the surge of New Zealand women in theatre to create feminist plays in the 1980s. These plays sought to highlight the reality of women’s inequality and struggles, critique patriarchal oppression, and inspire progress towards gender equality and the better protection of women’s rights.

Following on from my pieces about professional and cultural facets of Auckland Theatre, this article will explore 1980s feminist theatre in Auckland, with a focus on the experiences of acting women Elizabeth McRae and Andrea Kelland. In the 1980s, their theatre-careers followed a similar path; McRae and Kelland both acted in, and Kelland also directed, feminist plays in Auckland. Jean Hyland’s 2005 oral history interviews with these women have given me valuable insight into their perspectives on this dynamic period of their work.

Two compelling examples of McRae and Kelland’s feminist plays include: Secrets (performed in 1982 and 1987) and Virginia (1983). I will explore why they received both praise and criticism from Broadsheet reviewers, and how their venues (a 1982 Auckland Feminist Arts Festival, and the Mercury Upstairs Theatre) were sites of conflict and division.

By taking a microhistory approach, and closely examining Kelland and McRae’s work, I aim to provide a detailed picture of how their feminist plays empowered both themselves as female artists and the women in their audiences, yet also faced challenges and conflicts.

Secrets– An Example of Feminist Theatre’s Empowering Nature

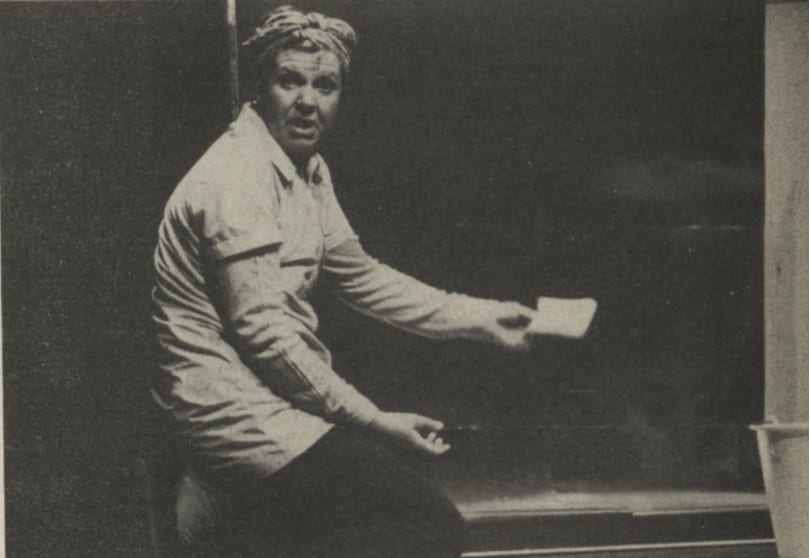

In 1982, Elizabeth McRae collaborated with Renée Taylor, an Auckland-based lesbian feminist playwright. McRae acted in a one-woman show, Secrets, by Renée. She played two contrasting characters. One woman was traumatised and obsessively cleaned kitchenware. She gradually revealed the sexual abuse she endured as a child from a male family member, and her fear that she could not protect her daughter from also being made unclean. The second woman was confident, even as she scrubbed the floors of a men’s bathroom. An unexpected twist reveals that this was her last day on the job, as she has won the Golden Kiwi lottery.

Elizabeth McRae in Secrets, Broadsheet, no. 102 (September 1982): 46.

Secrets was staged at the Playing with a Different Sex: a Feminist Arts Festival. The festival was organised by Debbie Tohill and Jenny Renals, and was held at the University of Auckland in June, 1982. It showcased feminist art, film, theatre, music, and dance.

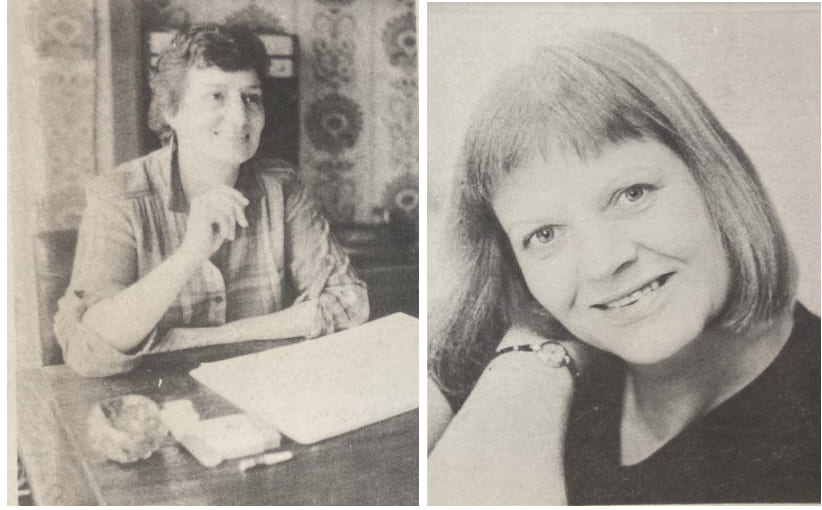

Renée (Left) and Elizabeth McRae (Right), photos from Craccum’s feature on the Feminist Arts Festival, June 1, 1982, 16. NZMS 1409 Elizabeth McRae Papers, Auckland Libraries Manuscripts Collection.

McRae remembered the audience’s response to her performance at the Maidment Theatre: “Well the audience just… took off… They yelled and screamed and clapped and they were so thrilled to see a feminist play, a play about women and about the things that they’d been thinking about.” The play’s success led to further performances at the Mercury Upstairs Theatre in July 1982. Reviewer Sandi Hall emphasised that for feminists who did not believe in the importance of theatre, the “click” would happen for them if they saw Secrets.

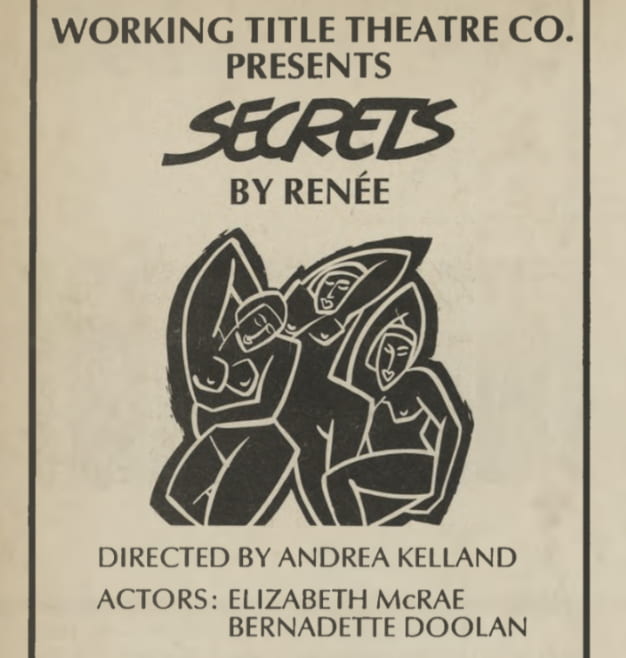

In 1987, Secrets was performed again, produced by the Auckland company, Working Title Theatre (McRae was on the committee). As McRae reprised her roles, Andrea Kelland joined as director. McRae described how the experience of being in an all-woman creative team was empowering: “[We were] taking control… There was a lot of female anger in the theatres where women were being exploited in a way, not used to their full potential…women’s stories not being told… We were making opportunities to work.”

Advertisement for the North Island tour of Secrets, Broadsheet, no. 148 (April 1987): 22.

Indeed, McRae, Renée and Kelland empowered themselves; they took control and made their own opportunities to tell women’s stories on the stage. The show that had begun in Auckland, toured the North Island in April-May, 1987, and was well-reviewed. Julie Sargison said Secrets showed “the experiences of New Zealand women; women I see every day, my next door neighbour, my friend, myself.” Indeed, the play represented the real, harrowing experiences of sexual abuse making women feel unclean, women working a job where they are underpaid or undervalued, women hoping for a miraculous lottery win-esque escape from patriarchal oppression, and mothers fearing that they could not protect their daughters. Sargison also noted how the title of Secrets was apt, because the play “unlocked the secrets” of women’s struggles that were often overlooked or viewed as shameful. She reflected on how this was empowering for women in the audience: “it is only… by women naming their experience that we can stop being victims, forgive each other and find ourselves.”

Secrets is just one of the feminist plays that McRae and Kelland took part in during the 1980s, but it provides a rich example of how Auckland theatre in this period was energised by the determination of women playwrights, actors and directors to both empower themselves as creators and the women in their audiences.

Cover of programme for Mercury production of Secrets, July 1982. NZMS 1409 Elizabeth McRae Papers, Auckland Libraries Manuscripts Collection.

Upstairs, Downstairs- Feminist Productions Appearing to Receive Limited Support

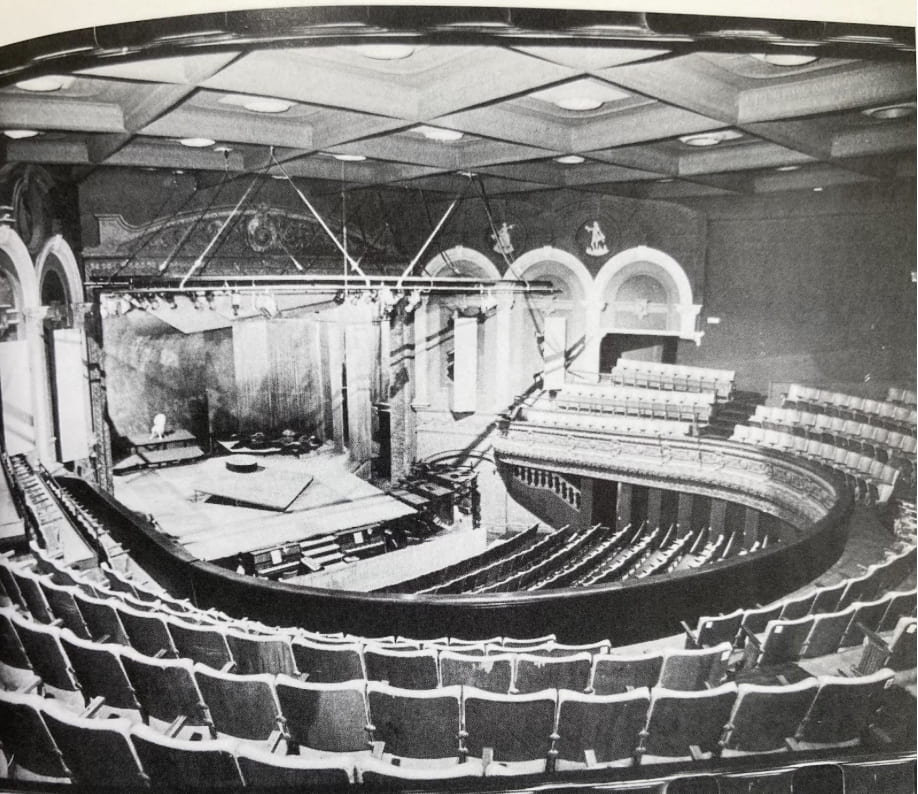

As Priscilla Pitts emphasised in Broadsheet, women gained more opportunities to write and direct plays within professional theatre companies in the 1980s. Elizabeth McRae’s productions with Renée had runs at the Mercury’s Upstairs theatre – a smaller studio space from the main stage downstairs. Similarly, Andrea Kelland acted in plays directed by Jan Prettejohns, to whom Mercury gave the green light to “put her finger on the pulse, the new feminist thing coming through.” Prettejohns and Kelland’s productions were also staged in the Mercury Upstairs (also known as the ‘Mercury 2’).

However, the division between the Mercury’s upstairs and downstairs theatres was noticed by Kelland, who felt the feminist plays were “very separate from what was going on downstairs… Downstairs they were doing ‘Foreskin’s Lament.”’

Advertisement for performances of Foreskin’s Lament at Mercury Downstairs. Included in a programme for a Mercury Upstairs production of Setting the Table, by Renée. Cast included Elizabeth McRae. September, 1982. NZMS 1409 Elizabeth McRae Papers, Auckland Libraries Manuscripts Collection.

Foreskin’s Lament challenged New Zealand rugby’s toxic masculinity and received a higher billing in the main theatre, whereas feminist productions, which arguably explored women’s issues in an equally insightful, honest and striking manner, were allocated to the smaller theatre. This may have looked to some observers like less support was being given to feminist theatre. History professor and member of the Auckland Theatre Trust (which set up and ran Mercury Theatre) Nicholas Tarling, recounted how Director Ian Mullins had composed a plan to “develop Mercury 2 as a venue for the non-popular plays, making the main auditorium available to more commercial shows, while providing an option for those who wanted to pursue minority interests.” Renée and Prettejohns’ feminist plays were staged upstairs, possibly because the Mercury had less faith in them being popular or commercially successful. The company may have believed the productions’ content would only appeal to the “minority interests” of second wave feminists, whereas more Aucklanders would prefer to be an audience and fill their larger theatre for plays like Foreskin’s Lament, that depicted New Zealand men’s issues.

The Mercury’s main auditorium, Nicholas Tarling, Wit, Eloquence and Commerce, A History of Auckland’s Mercury Theatre, (Auckland: Connacht Books, 2007)

Moreover, Kelland felt that the Mercury put on productions like Foreskin’s Lament, which had a majoritively male cast, “so they were able to employ all the boys in those plays.” She seemed to suggest that the Mercury put more effort into employing male actors and showcasing them in the bigger theatre, than they did into supporting women in theatre. Fiona Samuel, another acting woman interviewed by Hyland, recounted how at the end of her acting training in 1980, “all of the boys went to the Mercury Theatre” from her Wellington Drama school. By contrast, most of the female students were left “just swimming around… the Mercury took them all (as a job lot) because there always was a lot more work for men.”

Women playwrights, directors, and actors were increasingly taking the professional stage in 1980s Auckland, but professional theatre companies like the Mercury may have been reluctant to put their full support behind the growth of feminist and women’s theatre.

Moreover, McRae and Kelland’s feminist plays not only grappled with the uncertainty of receiving external support, they also contended with internal conflicts within the feminist movement. An exploration of the Auckland Feminist Arts Festival where Secrets was performed, and Kelland’s play, Virginia, reveals conflicts that occurred amongst Auckland feminists in the 1980s.

Feminist Arts Festival- Tension Behind the Scenes

Louise Rafkin reported in Broadsheet on the many “behind the scenes” criticisms and tensions at the June 1982 Feminist Arts Festival, which made for a charged context for Elizabeth McRae to perform Secrets in. Rafkin reported that Jenny Renals, one of the co-organisers, admitted that there was a “scarcity of Black women,” pinning the absence on the National Black Women’s Hui taking place in the same week as the Festival. Whilst Pākehā women like McRae wanted to take part in the Festival, Māori, Pasifika and other ‘Black’ women were likely more drawn to the Hui; perhaps viewing it as a space where their perspectives were more likely to be properly represented. This potential divide between the Feminist Arts Festival in Auckland and the National Black Women’s Hui, mirrored a significant tension in New Zealand second wave feminism. Feminists like Donna Awatere and Mona Papali’i frequently called out Pākehā feminists for being racist and failing to address issues significant to Black women.

There was also tension over ‘heterosexual exclusion’ because the Festival gave lesbian feminist artists (like Renée) a space to share their perspectives on women’s issues. Rafkin reported that heterosexual women “questioned their space in the Festival” because of “a large number of lesbians coupled with a large amount of portrayal of lesbianism in the various performances.” They felt excluded, due to “Lesbian Separatism.” Renals disagreed, insisting that “I didn’t see any evidence of “Lesbian Separatism.” She observed that “there were vocal feminists there which many women may have seen as such [as lesbians],” making their presence seem larger than it was. Kelland reflected on how the 1980s was an era that saw the “uprising of, and the coming out of lesbians.” Heterosexual women at the Festival who were shocked by the emergence and visibility of lesbian feminists, perhaps translated their shock into complaints of Lesbian Separatism. What was happening in the Arts reflected broader divisions between heterosexual and lesbian women in the feminist movement at the time.

Virginia– Representing Oppression or Removing Agency?

The play Virginia, directed by Prettejohns, and starring Andrea Kelland as Virginia Woolf, was linked to another debate in feminist circles; how to portray women’s struggles. It was staged at the Mercury Upstairs in July 1983. The script, by Edna O’Brien, portrayed Virginia suffering under the oppressive patriarchal forces of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As Cathie Dunsford summarised in her review of the play:

“The way limitations were imposed on Virginia by male writers and judges of ‘good’ literature, is subtly captured in the portrayal of Leonard Woolf. He patronises Virginia with every good intention until she feels like a lioness in a miniature cage.”

Dunsford pointed to Kelland’s moments of “caustic wit and rebellious spirit” as the best part of her performance, because she would have preferred to see far more of that strength evident in her character. She was highly critical of O’Brien’s version of Virginia, because whilst it “brought out a feminist perspective,” it did not do “justice to her strength or work.”

“Ultimately, Virginia became alternately the bitter tyrant and the sickly victim of an oppressive system, rather than the acutely aware political writer that she was… I left feeling as if A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas had never been written.”

Virginia encompassed an interesting conflict in interpretation. Prettejohns and Kelland, in bringing Virginia to the Auckland stage, sought to imbue Woolf’s life with a feminist lens and critique patriarchal oppression. However, Dunsford questioned whether the play was in fact disempowering for women if its portrayal of Virginia as a victim eclipsed her agency and power as an iconic female writer. The difficult question was raised: when feminists consider how a woman is oppressed, do they forget the strength she can also possess?

Closing Reflection

Elizabeth McRae and Andrea Kelland’s plays, and their venues of the Mercury Upstairs and 1982 Feminist Arts Festival, provide compelling examples of how feminist theatre in 1980s Auckland faced various challenges. Feminist theatre appearing to receive only limited backing from the Mercury, and encountering tensions between heterosexual and lesbian feminists, Pākehā and Black feminists, and conflicts of interpretation such as over the portrayal of women’s struggles in Virginia, reflected how Auckland second wave feminism could grapple with a lack of external support and internal divisions.

However, as Rafkin wrote about the tensions within the Feminist Arts Festival: “Despite these problems the important thing is that women were given space to perform… [the festival] showed that the feminist population in Auckland is alive, active, enthusiastic and reasonably large.” Whilst they encountered difficulties, we should not overlook the accomplishments of the surge of women creating theatre in 1980s Auckland. For instance, McRae and Kelland, by both acting in, and Kelland also directing, feminist plays, they empowered themselves as artists, and the women in their audiences. Feminist theatre was a vibrant artistic expression of the Auckland feminist movement which, despite facing challenges, inspiringly strove to empower women and progress closer towards achieving gender equality.

“Jumping for joy,” an illustration in Craccum’s feature on the Feminist Arts Festival, June 1, 1982, 18. NZMS 1409 Elizabeth McRae Papers, Auckland Libraries Manuscripts Collection.

My next and final article breaks away from acting women’s perspectives on developments in Auckland theatre. It narrows down to focus on the women themselves, and the pressures they endured in their careers.