Part One

How Auckland Ditched Rail for Roads and Rubber Tyres:

The good old trams

Part Two

Trams out; trolleybuses in

Part Three

The tube

Part Four

Motorway mania

Part Five

Conclusions

by Sam Turner-O’Keeffe*

Auckland has certainly improved its public transport system over recent decades. Its proponents will point to its new electrified trains, its Northern Busway and the relocation of its central city transport station to Britomart as all major successes.

Britomart Transport Centre, 2010, before Lower Queen Street was replaced with a public square. (Photograph by Brian Cairns. Reference: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1477-2521. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/123839#.Y8t3bm3KMsY.link)

Yet despite those advancements Auckland remains indisputably a congested, car-obsessed nightmare. In 2021, each of Auckland’s motorways recorded their worst-ever average commute times during morning peaks. Back in 2018 Aucklanders were losing 85 hours a year stuck in motorway traffic at peak hours, and during those times they averaged a speed of 42 km/h. Congestion like this has hounded Auckland for decades. At these rates, the future of Auckland’s transport system looks bleak.

Thankfully, Auckland bigwigs have planned at least two radical changes to the city’s public transport network. The first is the City Rail Link – an underground heavy rail deviation spanning from Britomart to Mount Eden, due to open in 2024. The second is Auckland Light Rail – a proposed modern tramway running directly to Māngere from the City Centre. Both projects are intended to entice Aucklanders out of their private cars while commuting, alleviating congestion on our roads.

The irony, though, is that between seventy to eighty years ago Auckland was presented with near-identical opportunities to invest in rail. Both were turned down. Instead of replacing its deteriorating tram network, Auckland chose to remove it entirely in favour of trolleybuses. Similarly, a proposal to electrify Auckland’s heavy rail system and build an underground deviation through it – almost a carbon copy of the City Rail Link – was abandoned when motorways were constructed instead.

It is difficult not to wonder what Auckland could have been like, had rail not given way to roads and rubber tyres. Could different decision-making in the past have saved Auckland from its gridlocked present?

Auckland’s trams: a background

From 1902 (the date of their electrification) onwards, Auckland’s tramways had formed the backbone of its public transport network. Replacing horse-drawn and steam-powered alternatives, these trams were fast, smooth and capable of running an incredibly frequent schedule. Aucklanders loved them, and patronage boomed. In 1903, the first full year of electric tram service, Aucklanders boarded their trams 13 million times. Yet 15 years later, in 1918 that figure had exploded to 44 million passengers per annum, and tram routes had expanded to cover (and form) most of today’s inner-city suburbia.

The inauguration ceremony of the Auckland Electric Tramway at the bottom of Queen Street, 17 November 1902. (Photograph by unknown. Reference: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 755-ALB39-11. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/photos/id/67682#.Y8uA3dcfQgU.link)

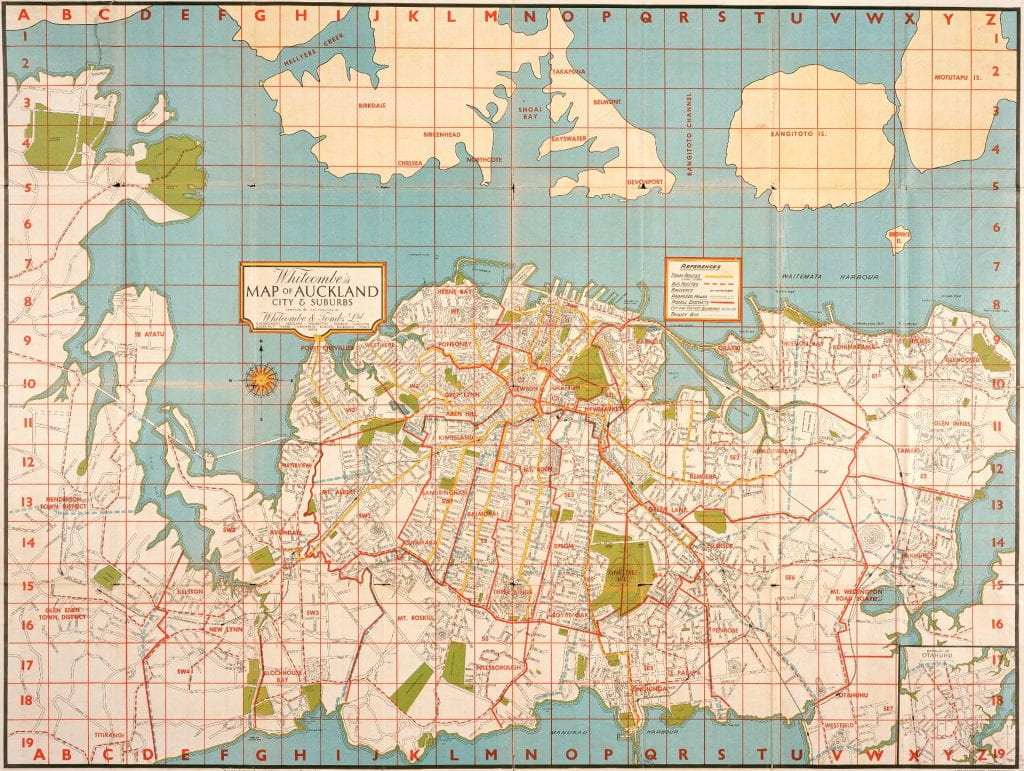

A comprehensive map of Auckland with its tram routes in yellow. Note how suburbia congregates around them. Date unknown, likely 1930s after September 1932. (Map by Whitcombe & Tombs. Reference: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 2447. https://kura.aucklandlibraries.govt.nz/digital/collection/maps/id/370#.Y8uDT7Qmono.link)

While the trams then faced competition from motor buses during the 1920s, and afterwards saw greatly reduced patronage (as all transport did) during the Great Depression, the general popularity of Auckland’s trams never seemed to be doomed. In 1926, Aucklanders made 63 million trips by tram despite the total population of Auckland City only numbering about 90,000 people. (Compare that to 2018-19’s 100.8 million public transport boardings – Auckland’s highest since 1951 – from a population of almost 1.7 million!) Similar figures were recorded at the end of the 1930s, even when the effects of the Great Depression were still being felt.

So, when and why did the Auckland Transport Board start pondering the trams’ replacement?

The first signs of such a mindset emerged at the very end of the 1930s and came from an unlikely place. In 1938, Queen Street was Auckland’s major shopping hub, attracting many into the central city from suburbia. Trams would take shoppers straight down Queen Street, where they could disembark and browse on either side of the road.

Farmers, a national powerhouse even then, had a department store in the central city. The problem was that it was on Hobson Street – and Hobson Street, despite running parallel with Queen Street, sat on top of a nasty incline. To encourage shoppers from Queen Street to browse their selection of goods, Farmers had taken to running a motor bus service directly up the hill, saving their customers an unappetising trek.

Yet in 1938 that all changed when Farmers chose to import four trolleybuses from England and hire the Auckland Transport Board to run those up Wyndham Street instead, because trolleybuses were better equipped for the incline.

Farmers Trading Company’s free trolleybus, Number 1, parked on Fanshawe Street for a test run. The chassis is painted light green and cream. (Photograph by unknown. 1938. 08/092/238. Walsh Memorial Library, The Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT). https://collection.motat.nz/objects/95472/farmers-free-bus.)

The project was a great success, with commuters wooed by the silence and luxury of the trolleybuses in comparison to local trams. The Auckland Transport Board’s annual report for 1939 certainly said as much: ‘… it is without doubt the most popular transport service in Auckland to-day.’ Such popularity also very clearly got the Board thinking about the future, with the report noting (rather vaguely) that while ‘the tramway service is modern, efficient and well-maintained… one foresees an increasing demand for new forms of transport’.

But a more potent threat to the future of Auckland’s trams emerged later. The following year World War Two broke out, and New Zealand started rationing fuel for use in the war effort. The consequences of this were significant: motor car use plummeted and bus services were slashed. The trams (relying on electric power) took up most of the burden – and they served not only those who would usually commute by other means, but also served entirely new or increasingly frequent commuters, including the onslaught of people searching for employment in the city centre and members of the Armed forces. Soon the system was being used to its absolute maximum. By 1941, every single tram in Auckland was being used to cope with evening peak times, and in each year until 1945 Aucklanders boarded the trams in record-high numbers.

The sheer intensity of this pressure laid on the tramway system, coupled with wartime shortages and supply issues, left the Auckland Transport Board incapable of maintaining the rolling stock and track properly; by the end of the war the tramways had deteriorated significantly. This meant that replacement of the trams and tramway infrastructure was no longer optional, but rather necessary, regardless of whether the Board sought to satisfy Auckland’s ‘increasing demand for new forms of transport’ or not. The new question, as the Auckland Transport Board conceptualised it, concerned what form replacement would take – whether it would constitute updating the tramway network to a modern edition, or ripping it out permanently in favour of something entirely different.

The next article will examine that dilemma.