Part Two

Te Whakapapa o Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua

The Whakapapa of Ngāti Te Ata

Part Three

The fluidity of Ngāti Te Ata rohe

by Tommy de Silva*

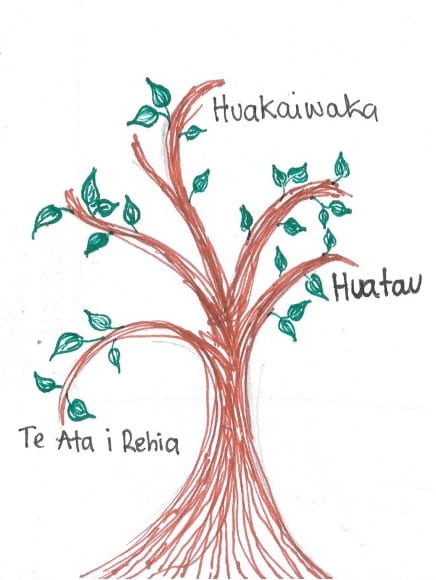

Whakapapa is an indestructible force within te ao Māori that connects tangata with their tūpuna, te taiao (the natural world) and one another. Māori gain a deep understanding of who and where we come from through whakapapa. Although whakapapa is often translated as genealogy, this is an oversimplification of a complex concept. Western genealogy does not recognise the intrinsic connection between tangata whenua and te taiao. Nor does genealogy explain the mana associated with understanding who and where you are from. Unlike genealogy, whakapapa is not fixed which allows for connections to seemingly distant people and places. For tangata whenua, understanding whakapapa gives an individual or group the key to the door to enact the mana of their tūpuna and collective. Through reading the roots of the Ngāti Te Ata whakapapa tree, from its ancient source through mai rā anō (the pre-Pākehā time) to the mid-19th-century, we can understand the Ngāti Te Ata claim to mana in Tāmaki. To appreciate the dynamic nature of Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua we must first acknowledge Te Whakapapa o Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua.

Te Whakapapa o Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua An important part of the Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua whakapapa tree, showing the direct connection between Ngāti Te Ata and Te Waiōhua through its namesake Huakaiwaka. Source: Commissioned Drawing One. 2022. Drawing on paper by Pellizzaro-Hurrell, Maya. Auckland.

Some of the earliest inhabitants of Tāmaki Makaurau were the Ngā Oho and Ngā Iwi peoples, two groups who were closely interrelated. Ngāti Te Ata traces our whakapapa back to these early groups, directly from their namesake ancestors .

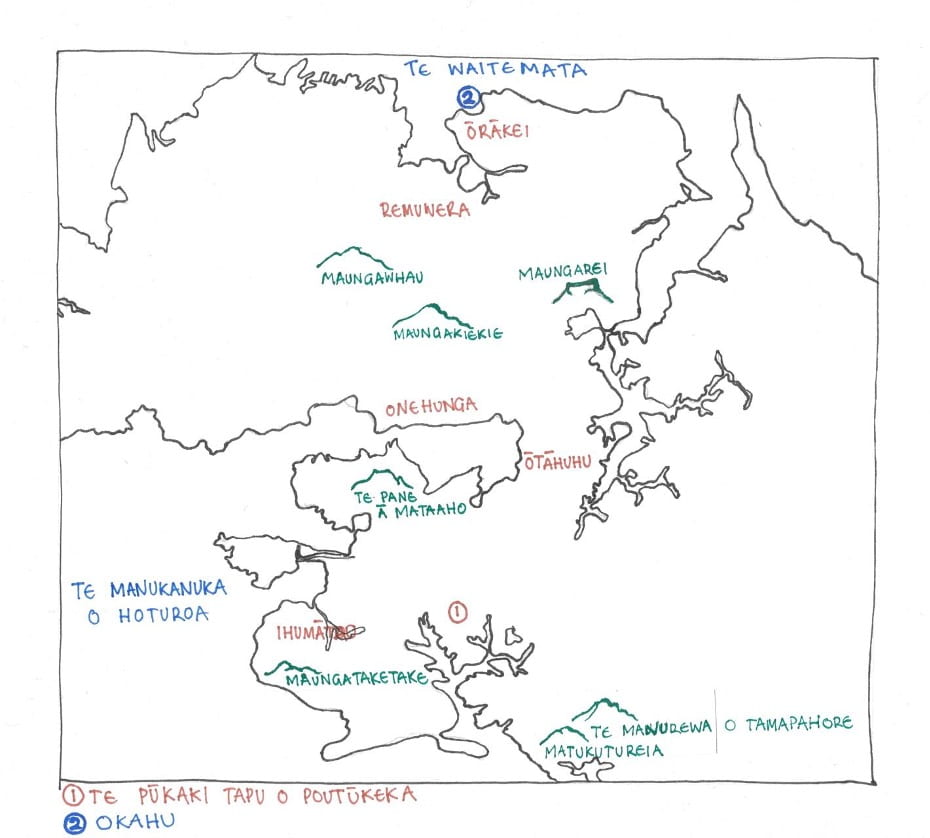

Some later arrivals in Tāmaki came from the Tainui waka, led by Poutūkeka son of the waka’s leader Hoturoa. Through the intermixing of Tāmaki’s earliest inhabitants and people from the some of the significant migratory waka, like Tainui, came the Ngāti Poutūkeka people. Early Ngāti Poutūkeka had a large presence around Mangere. Ngāti Poutūkeka fortified Te Pane ā Mataaho (Mangere maunga), cultivated the surrounding whenua and built kainga (settlements) adjacent to the maunga. Following the death of Poutūkeka, the ariki position (highest-ranking leader) was bestowed on his son Poutūkeka II.

A view of Te Pane ā Mataaho from Onehunga showing the impressive scale of the maunga compared to the buildings beneath it. Source: Richardson, James D. Photo 4-7731. 1931. Glass plate negative. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Heritage Images, Auckland.

Two sons of Poutūkeka II, Whatuturoto and Whaorakiterangi, greatly increased the Ngāti Poutūkeka rohe, and concurrently mana, in the Tāmaki region. Whaorakiterangi exercised mana over what we would now call the southern Manukau across to the western shores of Tīkapa Moana o Hauraki (the Hauraki Gulf). The domain of his brother, Whatuturoto, was the Tāmaki isthmus, and it extended south until hitting his brother’s rohe. Whatuturoto typically lived at Te Pane ā Mataaho but sometimes resided on the coast of Te Manukanuka o Hoturoa (the Manukau Harbour) from Maungataketake (Ellets Mountain) to Puhinui, an area which includes Ōwhatutūroto near the famous Ihumātao. Eventually Whatuturoto became ariki, and his son Huakaiwaka would also ultimately became ariki.

Map of Tamaki showing many of the named places from this whakapapa section. Note: this map has been copied from a modern day map, and as such does not represent a fully accurate depiction of the historical coastline. Source: Commissioned Drawing Two. 2022. Drawing on paper by Pellizzaro-Hurrell, Maya. Auckland.

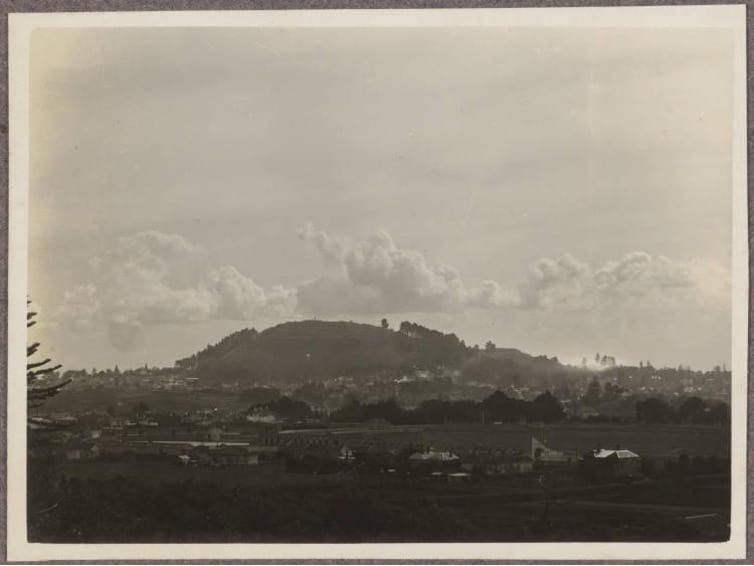

Much like his father, Huakaiwaka occupied Te Pane ā Mataaho, but he shared his residence between there, Maungakiekie (One Tree Hill) and Maungawhau (Mount Eden). Huakaiwaka also sometimes lived at other pā (fortified settlements) within the Ngāti Poutūkeka rohe, across an area extending east to Ōtāhuhu and south to Te Manurewa o Tamapahore (Matukutururu, Wiri Mountain). One of Huakaiwaka’s wives was Ruawhakiwhaki, and importantly for Ngāti Te Ata, one of the children from this union was Huatau. Huatau was part of the Ngāti Kahukoka hapū of Ngāti Poutūkeka. When near death, Huakaiwaka asked for wai from Te Pūkaki tapu o Poutūkeka, a tapu (sacred) spring southeast of Te Pane ā Mataaho. In honour of the ‘deathbed’ request of their former ariki, Ngāti Poutūkeka was renamed Te Wai ō Huakaiwaka, also known as Te Waiōhua. Through its earliest Tāmaki whakapapa, Te Waiōhua was fundamentally a branch of Ngā Iwi/Ngā Oho. Until displacement by Ngāti Whatua in the eighteenth century, Te Waiōhua led an economic union in Tāmaki that controlled regional trade and cultivations.

Maungawhau in its impressive grandeur as seen in the 1920s. Note the visible terraced slopes, a tell-tale sign of a former pā (tangata whenua fortified settlement, typically on hills or mountains). Source: Unknown photographer. Photo 755-ALB18-23-2 ‘Mount Eden’. Unknown date (1920-1929). Film negative. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Kura, Auckland.

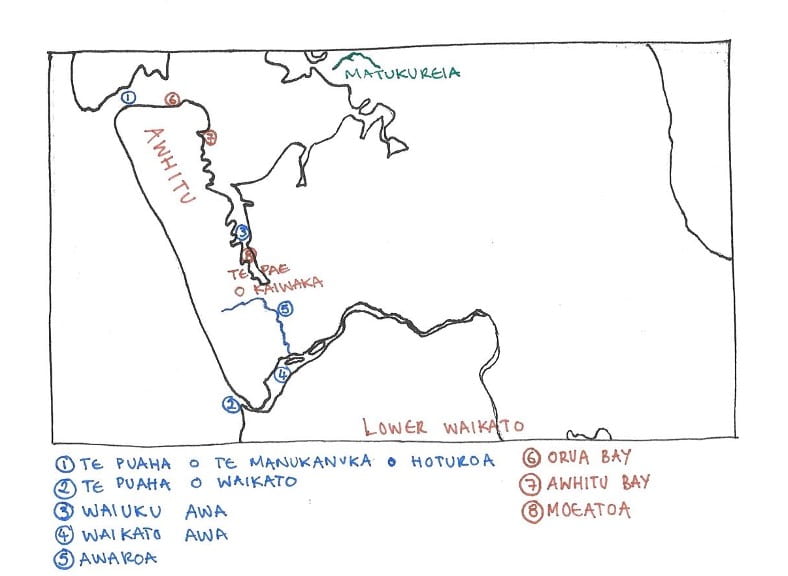

Huatau, son of Huakaiwaka and Ruawhakiwhaki, and the Ngāti Kahukoka hapū of Te Waiōhua lived primarily from the entrance of Te Manukanuka o Hoturoa to the mouth of the Waikato. This Ngāti Kahukoka rohe included the Awhitu peninsula. It was, however, at Matukutureia Maunga close to the Te Waiōhua heartland that Huatau’s daughter, Te Ata i Rehia, was born. Te Ata i Rehia had a Waikato husband called Tapaue. Tapaue was of Ngāti Mahuta. The union between Te Ata i Rehia and Tapaue greatly strengthened the bonds of whanaungatanga between Tāmaki and Waikato. Upon the death of their rangatira (leader) Te Ata i Rehia, Ngāti Kahukoka was renamed Ngāti Te Ata. Roughly three centuries ago, Ngāti Te Ata founded a primary marae at Te Pae o Kaiwaka, known later as Waiuku. Today Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua still exercises mana and kaitiakitanga in the aforementioned Ngāti Kahukoka rohe from the entrance of Te Manukanuka o Hoturoa to the mouth of the Waikato.

The northern portion of the Awhitu peninsula, commonly referred to as the Manukau Heads. Source: Hooker, Isabel. Photo JTD-07E03205 ‘From Huia Road to Manukau Heads’. 1941. Film negative. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Kura, Auckland.

The beginnings of both Ngāti Poutūkeka and Ngāti Te Ata were unions between descendants of the Tainui waka and early Tāmaki peoples, meaning that Ngāti Te Ata has a dual whakapapa. Consequently, our whakapapa deeply connects us not only to Tāmaki Makaurau but to the Waikato and her people. For example, the first Māori King, Potatau Te Wherowhero of Ngāti Mahuta from the lower Waikato, is a mokopuna (descendant) of Tapaue.

Potatau Te Wherowhero, first leader of Te Kīngitanga and descendant of Tapaue. Source: New Zealand Graphic. Record NZG-18900614-3-1 ‘Te Wherowhero (Potatau), the first Māori king’. 1890. Portrait. Auckland City Libraries Heritage Collections: Heritage Images, Auckland.

This whakapapa account lays out the foundation for understanding the Ngāti Te Ata claim to mana (in this context meaning political authority) in Tāmaki Makaurau, but it is not a definitive telling. Mana is not only about ancestral rights, it is also about exercising rangatiratanga and kaitiakitanga across successive generations. Ngāti Te Ata, through a history of ahi ka, has long exercised both rangatiratanga and kaitiakitanga in Tāmaki. Thus, the Ngāti Te Ata claim to mana in Tāmaki Makaurau is indisputable.

Nineteenth century Ngāti Te Ata history up until the 1860s

The early 1820s saw Tāmaki become a battlefield as waves of Ngāpuhi taua (war parties) devastated the local pā and people. By 1822, the chorus of gunpowder from the Musket Wars had reached Ngāti Te Ata rohe, setting our nineteenth century history off with an explosive bang (so-to-speak). In March of 1822, a Ngāpuhi taua, including the infamous Hongi Hika, attacked the Awhitu peninsula and was defeated by Ngāti Te Ata on the Waiuku Awa . The Musket Wars were fought on a scale of destruction that these motu had never seen before, and no Tāmaki rōpū was spared devastation. With the death and destruction of war comes the proliferation of dangerous, even deadly, tapu. As such, Tāmaki rōpū, including most of Ngāti Te Ata, abandoned the area and sought refuge with whanaunga in the Waikato or Hauraki beginning in the mid-late 1820s.

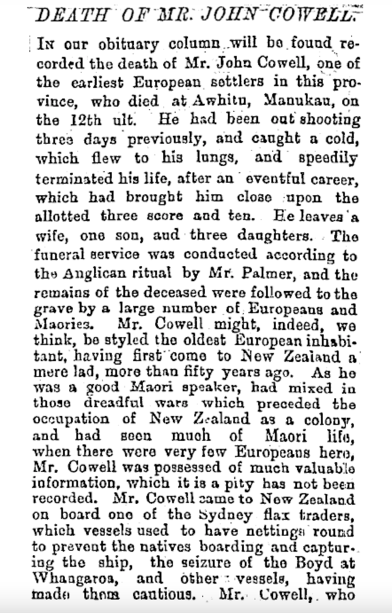

It seems that the rahui-esque abandonment of Tāmaki lasted until the mid-1830s. An ancestor of mine, the Pākehā-Māori John Cowell, noted that even in 1832, there was a noticeable lack of human habitation in Tāmaki. But during this time of relative abandonment, some Ngāti Te Ata maintained ahi ka in Tāmaki. Charles Marshall, a local trader, notes that in January 1832, he met a group of Ngāti Te Ata fishing at Pukaki in the Mangere area. Collecting resources, like fish, is an exercise of mana within an area. However, by 1835 ea was in part restored to Tāmaki. 1835 saw Te Wherowhero lead a group of musket-wielding Ngāti Mahuta and Ngāti Apakura to settle on the northern Awhitu peninsula. They aimed to protect Tāmaki from Ngāpuhi. With protection secured, displaced Tāmaki tangata whenua then returned to their turangawaewae.

Part of the New Zealand Herald obituary for John Cowell. Note that he died in Awhitu. John and his adoptive iwi Ngāti Apakura sought refuge in Ngāti Te Ata rohe, among other places, after their settlements were destroyed, people killed or imprisoned and their land stolen following the Waikato War. In a way Ngāti Apakura’s refuge in Awhitu was a reversal of the refuge Ngāti Te Ata sought with their Waikato whanaunga during the Musket Wars. Source: New Zealand Herald, Volume XVII, Issue 5837, p.5. Death of Mr. John Cowell. 1880. Newspaper obituary. Auckland.

Upon returning to Tāmaki, Ngāti Te Ata signed He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni. Signing this document was an assertion of Ngāti Te Ata mana and rangatiratanga. But the Tāmaki that was returned to was one of great change. The Pākehā had undoubtedly come. Ngāti Te Ata rohe and nearby areas became hubs for early missionary and trader activity relative to other areas in the region. For example, a mission station at Orua Bay (northern Awhitu) was first established in January 1836. Another mission was founded at Moeatoa (on the Waiuku River) in August 1836. The first trading station in the area was set up near the mouth of the Waikato in 1830 by Charles Marshall. The fact that a trading station was founded nearby to Ngāti Te Ata rohe during the apparent abandonment of Tāmaki highlights that local groups like Ngāti Te Ata never extinguished the fires of ahi ka. By 1836 several traders were active in the local area, such as John Kent. In 1840 another group of Pākehā, the Crown (the British authority), came ‘knocking on the door’ of Ngāti Te Ata.

From the first two 1840 meetings with Ngāti Te Ata, the Crown and their missionary aids were unable to secure any signatures to Te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi. However, at the Waikato Heads in either late March or early April 1840, four Ngāti Te Ata rangatira, Te Katipa, Maikuku, Aperahama Ngakainga and Wairākau, signed the Treaty. Then in mid-April a further two of our rangatira, Waiōhua Wiremu Ngawaro and Te Tawhā signed on the shores of Te Manukanuka, probably alongside the second signing of Te Katipa. The Ngāti Te Ata understanding was that by signing the Treaty, the group’s rangatiratanga and mana was being affirmed and acknowledged by the Crown. Interestingly, Te Tawhā and Wairākau were some of the only wahine signatories to the Treaty, carrying on the Ngāti Te Ata tradition of female leadership. Another signatory of the Treaty, Tāmati Ngāpora, was of mixed Ngāti Te Ata, Ngāti Mahuta whakapapa and he was Te Wherowhero’s cousin, highlighting the connection between Ngāti Te Ata and Waikato.

The Waikato-Manukau Treaty of Waitangi sheet (minus the signatories) signed by members of Ngāti Te Ata. Source: Archives New Zealand. Te Tiriti ki Waikato-Manukau | Waikato-Manukau sheet. 2017. Photograph. Archives New Zealand: Flickr. Wellington.

During his travels across Tāmaki in March 1842, Robert Sutton noted that Ngāti Te Ata rohe was by this time again numerously populated with many kainga. The year 1844 saw Ngāti Te Ata battle our neighbour Ngāti Tamaoho at Taurangaruru west of Waiuku. It was a short-lived conflict with peace quickly being somewhat reinstated. That same year some Ngāti Te Ata and Ngāti Tamaoho moved to Remuwera (Remuera) and Orakei to trade with Pākehā. Trade opportunities also came to Ngāti Te Ata at Waiuku. Waiuku sat at an important position along the Waikato-Auckland trade route thanks to the nearby water transportation network. As such, Ngāti Te Ata became an important and powerful actor in the Waikato-Auckland trade route that saw Waikato produce feed the growing colonial city. With trade opportunities came early Crown investment in Ngāti Te Ata rohe, who installed a road in the late 1840s that was improved upon in 1858. Also, Kawana (governor) George Grey commissioned a ship to service the Waiuku-to-Onehunga leg of the trade route. In August 1855, Charles Abraham noted that Waiuku was a particularly bustling place of trade in Tāmaki.

It seems that through these trade interactions, Ngāti Te Ata developed a positive, mutually beneficial early relationship with the Crown. At the same time, Ngāti Te Ata had a positive relationship with the burgeoning Kīngitanga movement, who the Crown saw as its enemy. Representatives of Ngāti Te Ata, including principal rangatira Te Katipa, were present at a large hui at Ihumātao in May 1857 where the Kīngitanga was discussed. Te Katipa was again present in June 1858 when Te Wherowhero was anointed kingi (king) by Ngāti Mahuta, Ngāti Maniapoto and Ngāti Haua. Here Te Katipa gave a speech after the anointment, potentially outlining his position that he wished for Te Wherowhero to be only a matua (senior figure) to Ngāti Te Ata as opposed to an outright ‘king’. Although at the time Ngāti Te Ata did not anoint Te Wherowhero as kingi, we still supported our whanaunga, for example, when we acted as a guard of honour for him on June 3rd 1858.

A map showing Te Pae o Kaiwaka (Waiuku), and the surrounding area. Source: Commissioned Drawing Three. 2022. Drawing on paper by Pellizzaro-Hurrell, Maya. Auckland.

Conclusion

The whakapapa of Ngāti Te Ata Waiōhua connects our more than twenty hapū to significant ancestral groups, individuals and places in Tāmaki and beyond. Through the intermixing of Ngā Oho/Ngā Iwi and Tāmaki-Tainui came our tupuna group Ngāti Poutūkeka. Ngāti Te Ata traces descent through several Ngāti Poutūkeka ariki: Poutūkeka, Poutūkeka II, Whatuturoto and Huakaiwaka. Our whakapapa then runs through Te Waiōhua, who became the undisputed hegemon of Tāmaki. From the Ngāti Kahukoka hapū of Te Waiōhua came Ngāti Te Ata as we are known today, named after our wahine toa (female warrior) ancestor Te Ata i Rehia.

Although neither the whakapapa nor history I provided in this post are definitive, they both highlight the indisputable Ngāti Te Ata claim to mana in Tāmaki. Our history is one of ahi ka in Tāmaki Makaurau, yet Ngāti Te Ata have also always acted upon our special relationship with the Waikato and her people. Indeed, it is fitting that today the Auckland-Waikato border runs just south of Waiuku. The next article in this series begins my look at the fluidity and flexibility of tangata māori, starting with rohe (territory).

Kupu Appendix

- Ea | The state reached after a wrong has been corrected through the restoration of relational balance via compensation of some form.

- Kaitiakitanga | The tikanga of Māori sustainable resource use to preserve resources for future generations.

- Kīngitanga | A movement founded in the late 1850s to stop land theft by installing a Māori monarch under whom land could be vested in.

- Pākehā-Māori | Important early intermediaries between Pākehā and tangata whenua, Pākehā-Māori were Europeans or other outsiders who became part of tangata māori society, speaking fluent te reo, fighting in local conflicts, living in tangata whenua communities and marrying into local groups. Many were traders of some sort.

- Rahui | A ritual restriction on a certain area or resource to protect people from dangerous tapu or to protect and conserve a resource.

- Rangatiratanga | The exercise of authority by a leader who weaves a group of people together in the process.

- Tapu | Refers to the Māori idea of sacredness.

- Turangawaewae | Homeland of sorts, referring to a place where someone has belonging to through whakapapa.

Whanaungatanga | A central and vital tikanga that refers to relationship and community building and maintenance.