Part Two

Auckland Acting Women’s Experiences within Early Professional Theatre Companies

by Anna McCardle*

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Auckland theatre scene was becoming professionalised, after decades where amateur productions had been the norm. Mercury Theatre was founded as Auckland’s first professional theatre company in 1968, staging many performances in its central city theatre. Theatre Corporate, a professional company, distinctive for its engagement with and tours of Auckland and North Island schools, began shortly after in 1973. Jean Hyland’s oral history interviews with Auckland acting women provide insight into these emergent companies. Hyland spoke with Elizabeth McRae, who acted in Mercury Theatre from their first 1968 show, and Andrea Kelland and Linda Cartwright, who performed at schools in Theatre Corporate through the 1970s. Examining their experiences builds an informative picture of the companies’ invigorating yet challenging working conditions.

“At Last”: Receiving Payment for Acting Work

Auckland amateur theatre productions, which Elizabeth McRae had performed in prior to starting with Mercury Theatre in 1968, did not generally pay their actors. They were passion projects; the enjoyment and satisfaction of voluntarily putting a show together was the reward for work, rather than payment. McRae was able to be paid for her voice acting in radio plays before she was for her theatre acting.

The move by Auckland professional theatre companies to pay actors for their work after 1968 marked a significant change; theatre acting became more than a passion project, it became a viable job. “At last,” John Cowie Reid proudly proclaimed in the programme of Mercury Theatre’s first production, “our own actors… can find employment in a New Zealand civic theatre.” Mary Amoore, founder of the Central Theatre, an Auckland amateur theatre company, was positive about the rise of professional companies. She thought that the beginning of payment showed how more “acceptance” was being shown towards actors in New Zealand.

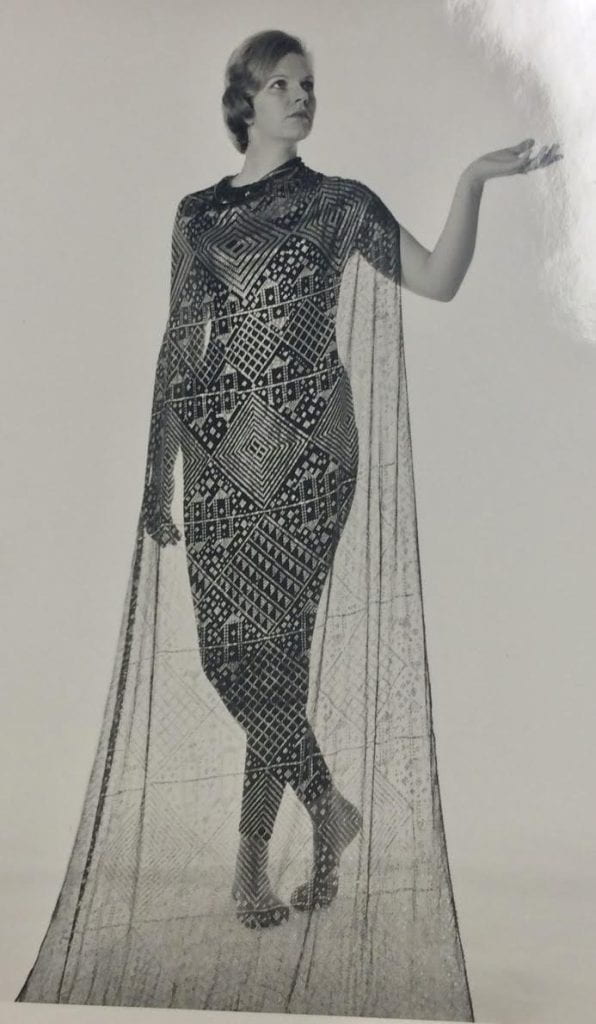

Portrait of Elizabeth McRae, foyer photograph at Mercury opening night, May 1, 1968, photo by Noel Brotherston, Elizabeth McRae papers,. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.

McRae remembered how as an actor in the Mercury, “you felt…you really had a responsibility to keep yourself fit and your voice right and do your [acting] exercises … the fact that you were being paid was really different.” She was conscious of the newness of being paid, and the difference it made in motivating actors to perform at a high standard. Linda Cartwright felt “the excitement” of being a paid professional, and regarded the emergence of companies like Theatre Corporate as “the golden age of theatre because you had ….year contracts. That’s just amazing, so you never had to worry about earning your living.” Having year-round employment provided stability and reassurance that actors had a fairly long-term-paid placement within the company. However, Andrea Kelland questioned the entire premise of acting needing to be paid in order for it to qualify as professional: “[Professionalism] is a state of mind isn’t it?…I’m a professional actor… whether or not I get a living wage from it.”

“The Money Wasn’t Great”

Because these newly-emerged Auckland professional theatre companies were embarking on an unprecedented and risky venture, they often struggled with making money. This led to them frequently being unable to pay their actors well. Linda Cartwright remembered her earnings at Theatre Corporate being around $30 a week in rehearsals, and $50 while touring. She felt that “the money wasn’t great… They always paid us, bless their hearts, no matter how much the theatre was struggling.”

The acting women Hyland interviewed had varying perspectives on whether their pay was sufficient. Elizabeth McRae, who had a breadwinning husband, felt that “people unlike myself who was a ‘kept woman’… could live on it [their pay]. They could pay their rent for a flat in town.” She thought that people in situations like Cartwright and Andrea Kelland, who were both single and had their acting jobs as their main sources of income, were fairly stable. Cartwright was similarly optimistic, “if you’re following your heart and doing what you want you are happier anyway… I could live on $50 alright.” Dealing with the difficulty of living on low pay was worth it, as long as she could pursue her passion professionally.

By contrast, Kelland did not feel particularly stable in only earning just enough to meet essential costs: “there wasn’t much left out of thirty dollars a week… We were just paying our rent and putting our money into the kitty.” She remembered how Theatre Corporate frequently did not have enough money to pay the actors during their Christmas holidays, which would force those who could not make rent to move out of their flats and back in with their parents during that period. This raises the question: who was excluded by the low pay? Were the people able to pursue this new professional acting mainly those who had a breadwinning partner or supportive family they could fall back on? Being able to make your passion a career path, even when it is not particularly lucrative, shows that you likely have financial support systems behind you.

“Concentrated Effort”: Intense Workload of Professional Companies

Elizabeth McRae noted how the workload increased considerably in transitioning from amateur to professional theatre. She had typically spent around two to three months rehearsing an amateur production a few nights a week, whereas at the Mercury a show needed to be ready to perform after three to four weeks of rehearsing every day; a faster turnover of shows was needed for Auckland audiences whose attendance and interest subsidised Mercury Theatre.

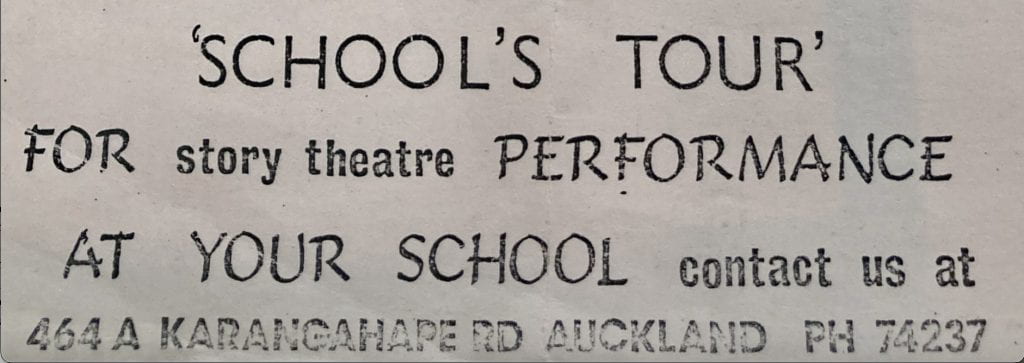

Advertisement for Theatre Corporate school tours, Back in the Dreamtime programme, June, 1975, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections, EPH-06192

Similarly, Theatre Corporate’s touring shows were in demand at Auckland and North Island schools. Andrea Kelland remembered the company being booked for four shows a day, and if they had performed at Auckland schools, they would return to their theatre base afterward and rehearse more shows. Linda Cartwright described a possible daily schedule as waking up early, driving to a Hamilton school to perform, then they would “come back. Maybe have a costume fitting, maybe an Auckland school in the early afternoon and then perform at night.” The schedules were rigorous.

McRae appreciated being able to shift from part-time amateur theatre, to devoting immense time and energy to Mercury shows: “The concentrated effort was so good… suddenly you felt you were being pulled up by your bootstraps.” Cartwright felt similarly: “I can remember thinking ‘my God I’m spending more time on the stage than I am off’… but then we loved it you see, so it didn’t feel like work.” However, whilst the actors’ hard work came from a love for performing, there was also awareness that such hard work was vital to keeping the Mercury and Theatre Corporate up and running. The actors played a key role in ensuring their companies were continually performing shows, attracting audience attendance, and acquiring enough profit and success to continue what they had only just begun as emergent professional theatres. The pressure would not let up easily. As Cartwright recalled: “We felt very responsible at the beginning for holding the theatre up. You were very aware that if you were ill one night and didn’t go on stage acting, then it could be the difference between the theatre continuing or not continuing.”

“Not a Star System”: The Professional Companies’ Team Environment

Due to a professional company like Theatre Corporate providing year-long contracts, Linda Cartwright felt “safe and secure” in her job, and this job security made it easier for her to get along with her co-actors; “you don’t have to bad mouth anyone [to ensure you got a job instead of them].” Everyone knew they already had contracts, and would be working alongside each other in numerous shows for at least a year. As a result, the competition amongst members of a professional company was likely not as vicious as it can be between actors who have to continually audition to gain short-term employment in yet another advertisement, play, TV show or film.

The sense of being a stable company of actors fostered a strong team environment. Elizabeth McRae remembered how at the Mercury, “When people are working together a lot, play after play… you read each other so much more easily and it’s a great joy.” Shows were more seamless and effective when the actors could grow to understand one another’s style and craft over time.

Mercury actors advertising The Canterbury Tales in Queen Street, 1971, Nicholas Tarling, Wit, Eloquence and Commerce, A History of Auckland’s Mercury Theatre, (Auckland: Connacht Books, 2007)

Cartwright expressed that she disliked the “Hollywood hype that goes round and the gossipy nature of stars… I don’t really believe in a star system, I do believe in an ensemble, that every actor in that theatre is a star whether they’re playing a small part or a big one.” She came to feel the star system of venerating individual acting idols was not as shiny as it may seem to some, through valuing her ensemble experience in Theatre Corporate.

Moreover, the long hours and intensity of rehearsing and performing show after show, could push one to form strong and long-lasting bonds with the castmates they spent most of their time with. Andrea Kelland and Cartwright both recalled that they still had a strong affinity when they bumped into each other decades after working at Corporate, because of everything they went through in touring schools together for years.

“Not a Planet, but a Comet”: Closing Reflection

The emergence of professional theatre in Auckland significantly impacted the acting women Hyland interviewed, imbuing their work with an array of benefits and challenges. The Mercury and Theatre Corporate, as new companies, were not always financially stable and were under pressure to produce a high output of shows. Hence, the acting women frequently had to contend with low pay and exhausting workloads. Despite these challenges, Elizabeth McRae, Linda Cartwright and Andrea Kelland loved being a part of these professional companies. They felt the excitement of theatre-acting finally being paid and viewed as a job, appreciated the bonds and team environment formed with their fellow actors, and valued the opportunity to channel all their passion for acting into rigorous schedules of constant rehearsals and shows. Cartwright called the late 1960s and early 1970s beginning of professional theatre companies in Auckland, the “golden age of theatre.”

Cartwright missed this golden age. Mercury Theatre closed in 1992 due to financial difficulties. Theatre Corporate, according to History professor Nicholas Tarling, “collapsed” in 1986, likely also due to financial strain. Although these types of theatre ventures are perhaps too difficult to replicate in the present day, Cartwright viewed theatre companies like these as the ideal.

Cartwright disapproved of contemporary actors having to audition for short term work on project after project, “grabbing” opportunities where they can; “You [are]… doing nothing for three months and then you get two jobs and you have to choose between them and you choose one and that falls through.” She believed that modern actors work in a more individualistic, competitive and insecure field, compared to the stability and collectivism offered by a year-long contract at a company like Theatre Corporate: “I still believe that the best possible way of being a working actor is to be in the theatre on contract for some long time… you are part of a company… you know your fellow actors so well.” Tarling felt similarly to Cartwright. He wrote with regard to Mercury Theatre, “What was named after a planet turned out to be a comet… Without a theatre company structure it seems impossible to build on what was achieved in the 1970s and 1980s.”

My next article will shift away from the professionalisation of Auckland theatre. It will continue to examine the Mercury, but also a company called Pacific Theatre, founded by actor and director Justine Simei-Barton. These two companies, as case studies, demonstrate how significant cultural conflicts and evolutions unfolded in late 1960s-1980s Auckland theatre.